Lloyd Allayre Loar

Lloyd Loar’s contributions to stringed musical instruments rank him among other musical geniuses such as Antonius Stradivari, Orville Gibson, Leo Fender, and Christian F. Martin. The legacy of their craft and the contributions they made exceed the merits perceived in their time, and they established the criteria by which all stringed musical instruments are measured today. But one might suggest that Loar was just a cut above the rest. His approach to the science of music (to which his 15 patents attest) and the acoustical properties of the instruments he created, bear no equal. He was one of the earliest pioneers to amplify instruments electrically, and in his search for excellence, he created a keyboard instrument that would never go out of tune. (When I uncrated one of Loar’s personal instruments 50 years after it was packed it for storage, it was still in perfect pitch – every note!) Possibly even more important is that this was an electric keyboard whose design was decades ahead of its time.

What further separated Loar from the rest is that he was a musician – not a luthier – with an overwhelming interest in instrument construction, a rich understanding of musical acoustics, and the undying quest to design instruments that produce elegant tone.

The Early Years and Education

Lloyd Allayre Loar was born on January 9, 1886 in Cropsey, Illinois, a tiny farming town about 120 miles southwest of Chicago. (The population in 2022 was about 200.) Lloyd was the son of George F. Loar (1858-1933) and Clara Moore Green Loar (1860-1929) who were married on November 24, 1884. Lloyd, the oldest of three children, had a brother Raymond (born July 10, 1888), and sister Madelon (born April 21, 1900). Like Lloyd, Madelon was interested in music, and both she and Lloyd were influenced by their father.

Some members of the Loar family in 1897. Back row (L to R): Clara Loar, George Loar, Emma Loar Gaddis. Center row (L to R): Raymond Loar, Lloyd Loar. Front row (L to R): David Loar, Thomas Loar, Laura Loar. Lloyd was 11 when this photo was taken. Sister Madelon was born three years later.

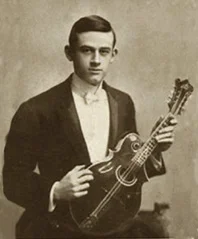

In 1906, at 20 years of age, Loar was performing professionally with an unusual Gibson three-point H4 mandola that had no lower body point. During this period, he was a member of the Fisher Shipp Concert Company whose members included Loar, Fisher Shipp, Etta Goode Heacock, and Louis G. Karnes.

Lloyd attended Lewiston High School from 1899 to 1903 and showed special interest in physics and geometry, in which he likewise received good grades. While in high school, Lloyd began performing in local music programs. At age 18, he entered the Oberlin Conservatory (Ohio) to study harmony, orchestration, canon, counterpoint, fugue, music theory, and piano. By 1906, when Lloyd was just 20 years of age, he was performing skillfully and professionally on Gibson and Martin mandolins in both solo and concert settings, and he was equally proficient on piano, violin, viola, and mandola.

Entering the business of music

In 1906, Loar met a female singer named (Sally) Fisher Shipp (1878-1954), the leader of the well-known Fisher Shipp Concert Company, and he was invited to join her ensemble. The Fisher Shipp Concert Company performed on numerous concert tours throughout the central and eastern states.

Loar’s personal and professional relationship with Fisher Shipp was blossoming, leading to their marriage in 1916. When Loar was engaged to promote the “Gibsonian Orchestra,” Fisher was included as the vocalist. Here Loar (second from right, front) is performing on an F4 mandolin.

The Fisher Shipp Concert Company, ca. 1925. Here the ensemble featured Loar (L), Dorothy Crane, Fisher Shipp (standing), James H. Johnstone, Nell VerCies, and Lucille Campbell (Nell is holding Loar’s 10-string mando-viola).

Joining Gibson

Although there is little question that Orville Gibson himself was the seed for the 100+ years of great instruments that have grown from his creativity, Orville’s ideas were further cultivated by numerous loyal Gibson employees who followed after Orville’s departure from the company in 1908 (Orville left Kalamazoo in 1918 to move back to his home state of New York). The list of these contributors is too long to include here, but one name stands out from all the rest: a young man named Lloyd Loar.

The year 1911 marked the time that Loar began his official relationship with The Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co. of Kalamazoo, Michigan as a performing artist, a participant in many Gibson-sponsored traveling “Gibsonians” bands, an advisor, and a music composer. By 1913, Gibson was publishing numerous musical arrangements that Loar had prepared for the company.

A Gibsonans banjo ensemble, from left: Crane, Shipp, Loar, Johnstone, Campbell, VerCies. (Loar is playing an MB-5 mandolin-banjo and Nell VerCies has Loar’s TB-5.

By 1914, Loar was engaged as concert master for Gibson’s Gibsonian ensembles, writing and arranging much of the music they performed. His assignment was to ensure that the demonstration of Gibson’s instruments by the various traveling groups would entice audiences with the best of Gibson’s voicing, elaboration of musical content, and, of course, the intricacy of the ensemble’s performance.

In early 1918 Loar received a contract assignment at Gibson as acoustical engineer and also became responsible for various business management functions including the management of Gibson’s Gibsonian band/orchestra marketing program. However, the impact of World War I and the potential of studying music in Europe motivated him to sign a one-year contract with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to be a concert entertainer and organizer of bands to perform for the troops in Europe during WWI. Loar had a Red Workers Permit (RWP) – a form of passport issued to all non-military personnel going to Europe during WWI – that he obtained through the Y.M.C.A. He sailed from the United States on November 1, 1918, arrived in France on November 8, and reported for duty on November 9. But before Loar could rosin up his bow and perform for the troops, the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 and the War was over – Loar’s work there was done before it even began. After six months into his AEF contract, Loar was able obtain a discharge. In his Red Cross records, his Reason for Leaving is entered as “illness – honorable discharge” and under Plans for Return it is entered that he was “undecided, probably returns to former work, concert musician.”

Since the war was over and his services were no longer needed in Europe, Loar took advantage of his time there to study with Paul Vidal at the National Conservatory of Music, and attend the National Institute of Radio Engineering, both in Paris. He stayed in Europe a few months after his discharge and upon his return to the States in June of 1919, Lloyd went back to Gibson as a contractor working as credit manager, design consultant, and again as an acoustical engineer.

While working at Gibson, Lloyd continued his education at the Chicago Musical College in the second and third ten-week sessions of the 1919-1920 school year studying Harmony with Louis Victor Saar and composition with Felix Borowski (then president of the Chicago Musical College). And, in 1921, Lloyd received his Master of Music diploma in Theory and Counterpoint from the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. That same year Lloyd Loar won first prize in a contest for American composers staged by the National Federation of Music Clubs.

When Loar was working in Kalamazoo for both Gibson and for ViVi-Tone, he lived in this 2-story home at 315 Woodward.

Loar had ideas to improve Gibson’s mandolin construction, and it wasn’t long before Loar presented himself as a candidate for employment to Sylvo Reams, Gibson’s General Manager and one of Gibson’s original investors and stockholders. But Reams didn’t hire Loar immediately, and it wasn’t until Reams’ passing in 1917, when Loar’s friend Lewis Williams (also one of the original investors) became General Manager that Loar was brought on board as a full-time employee in February, 1920.

Loar began his fame as a musical instrument developer while working for Gibson. His most obvious contributions to Gibson were the design and development of the “Master Model” instruments including: the F-5 “Master Model” mandolin, H-5 “Master Model” mandola, K-5 “Master Model” mando-cello, L-5 “Master Model” guitar, and “Master Tone” (later to become “Mastertone”) banjos. While it is uncertain whether the product names actually were derived from his nickname, or vice versa, to his peers at Gibson and to the music industry at large, he was known as “Master Loar.”

In addition to being away from the factory from time to time because of his touring with the Gibsonian bands, he was also on the road with The Fisher Shipp Concert Company during July and August each year. As a result, today we find very few “Master Model” instruments that were signed and dated by him in late July or during the month of August. Further, since there were no hand-tuning properties that could then be attributed to the banjo’s body, none of the Mastertone banjo models bore a Lloyd Loar “approved by” signature label. It is also important to note that Gibson was producing a large quantity of standard model mandolins, mandolas, and guitars (other than Master Models) depending on immediate sales, sales forecast, and inventory. Thus the Master Models were not the only instruments vying for assembly and finishing at any one time.

Many believe that Lloyd Loar was a luthier who built instruments at Gibson and then tested and signed them. While it is true that he signed the labels – at least initially – Loar was not a luthier, and he did not work at Gibson as an instrument builder. He was a musician who had an intense interest in musical acoustics, and in his role at Gibson, he guided the design and development of several instrument models and accessories. With the exception that Loar was a musician employed by Gibson, his contribution to Gibson’s instrument line was similar to that of Les Paul (1915-2009) whose ideas and input led to Gibson’s growth and expansion in solidbody electric guitars. And, of course, numerous other musicians have had relationships with Gibson through the years resulting in models being named after them. Further, Loar lived in Kalamazoo and was at the plant regularly while Les Paul lived in New Jersey and was at the plant only occasionally.

In a letter dated January 13, 1921, Lewis Williams clearly outlined Loar’s duties at Gibson to include his work as acoustical engineer, filing patents, managing the Department of Repairs, training service agents, and more. Loar was also responsible for implementing his “technic” – the art of tap tuning. (For complete details of William’s letter, see The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar.)

Loar’s involvement at Gibson went beyond being an acoustical engineer and instrument designer. One of the jobs Williams assigned Loar to do was to be responsible for the service agents. Here we see Loar (standing in back of room, center, to right of blackboard) with a group of Gibson’s sales and service agents. Note the music notation on blackboard; most probably depicting the musical range of Gibson’s line of acoustic stringed instruments.

Loar’s first 10-string mando-viola was made by Gibson and had a pear-shaped body and featured an oval soundhole. The instrument was similar to the size and construction of the H-2 mandolas of the period.

This photo of Loar was published in many of Gibson’s early catalogs and entitled “R&D Department.” It shows Lloyd with his 10-string mando-viola (shown below), at the Gibson factory at 225 Parsons Street, Kalamazoo, Michigan, ca.1924. From careful investigation of the building, it appears this photo was taken on the ground floor, along the western wall. Loar was about 38 years of age at the time this photo was taken.

In about 1920, Lloyd had Gibson construct a custom pear-shaped mando-viola with an oval soundhole and features that were similar to the H-2’s of the period. It was a unique instrument that united the qualities of the mandolin and viola: a “mando-viola” boasting five courses (two strings each) that Loar tuned Eb, C, F, Bb, and Eb (treble to bass).

Around 1924, as the features of the F-5 mandolin and H-5 mandola were taking shape, Loar had a second custom mando-viola constructed. This second instrument also featured a pear-shaped body but also took advantage of the new features of the Master Model instruments with 𝑓-holes, graduated soundboard and backboard, longitudinal tone bars, tap tuned body, steeper neck pitch, and an elevated fretboard extension. And, this second mando-viola included a Virzi Tone Producer. Loar’s mando-viola with 𝑓-holes is seen in the photo of Lloyd in the “R&D Lab” photo below. This instrument, including Loar’s musical saw (hanging on the back wall behind him in the photo above) and electric viola, were fitted in a single case and was in my private collection for 15 years. (If you are interested in hearing the mando-viola, I loaned it to David Grisman for use in the “Wayfaring Stranger” cut on his album entitled Dawg Grass that was released in January, 1982.)

Loar’s 10-string mando-viola, electric viola, and musical saw were kept in one carrying case. (The electric viola was a prototype for ViVi-Tone, therefore this case had to have been made in the early 1930’s.)

Loar was highly motivated by the work of the great violin makers and sought to include their features in the development of Gibson’s fretted instruments. And, it was these features that made Gibson’s fretted instruments outstanding. These included: fully graduated soundboards and backboards, a minimum-thickness area (today referred to as a “recurve”) around the entire soundboard, longitudinal tone bars, f-holes, longer necks (i.e., access to a greater playable range of the fretboard) that connected to the body at the 15th fret, elevated fretboards (above the soundboard), ebony fretboard extender, increased neck pitch from 4° (of the F4) to 5-1/2° to achieve a 16° string-break angle (over bridge), and most importantly, Loar’s “technic” – as Lewis Williams called it – for tap tuning the tone bars, soundboard, backboard and air chamber. While all of these attributes are important, I believe Loar’s major contribution was the introduction of his “technic” of tap tuning. This process ensured the correct stiffness of the soundboards, backboards, and tone bars by tuning them to specific notes that were a quarter tone off concert pitch. Realizing that stiffness and pitch were inextricably related, tap tuning ensured reliable and repeatable construction and tone from instrument to instrument. Further, the size of the f-holes was adjusted to tune the air chamber to a specific note. Here, Loar drew from both the great acoustical engineers of the day as well as from the heralded violin makers. (For more details on the tap-tuning process read The Art of Tap Tuning by Roger Siminoff, available from siminoffbooks.com.)

In Loar’s Physics of Music class at Northwestern University (1930-1943) Loar spoke of Stradivari’s tuning process: His greatest improvement, and one which took much research to discover, was attuning the tops and back. He would set the pitch so that the front was a quarter of a tone higher [than the backboard]. This tuning feature, as adapted by Gibson under Loar’s guidance, is what sets these instruments apart today. It was also what made them difficult to produce in a manufacturing environment and ultimately led to the demise of the tap tuning process at Gibson after Loar’s departure from the company in October of 1924. (Structural tuning returned to Gibson in the 1970s under the watchful guidance of Richard Schneider and Dr. Michael Kasha in the introduction of the Mark Guitar, and again in 1978 when I was invited to champion the introduction of the F5L mandolin.)

It is important to note that Loar was not the first to suggest the use of 𝑓-holes, elevated fretboard extensions, and arched soundboards and backboards on mandolins. Another instrument designer named Albert Shutt of Topeka, Kansas filed for a patent that claimed these features on December 6, 1909 and was granted U.S. Design Patent 40,564 on March 8, 1910 – a patent that had a life span of seven years. In essence, these features were on the market and accessible to the public long before the development of Gibson’s F-5 mandolin, and it meant that Gibson could begin using these features on mandolins, mandolas, and guitars as early as 1917 when Shutt’s seven-year patent expired. While we know nothing of the relationship between Gibson, Loar, and Shutt – if any – it begs the question of just how many of these ideas came directly from Loar and how many were borrowed from Shutt. Regardless, Gibson was a well-established instrument company and had the manufacturing and marketing muscle to include these features in their instruments to expand its mandolin and guitar business.

Lloyd’s work on banjos was equally astute. Loar developed a new banjo design with a hollow tubular tone chamber supported by spring-loaded ball bearings. This instrument was the foundation of the heralded Gibson Mastertone banjo line and the many pot-assembly hardware derivations that were to follow. However, Loar was asked to relinquish and sign away the rights to this banjo tone chamber design, and rather than the credit going to Loar, the patent for the spring-loaded ball-bearing tone chamber was filed by George Altermatt months after Loar left Gibson.

Loar became enamored with the work of violin distributors and makers Joseph and John Virzi of New York. The Virzi brothers promoted their line of fine German violins, and as an outcropping of their instrument sales business, they created and patented a “complementary amplifier” called the “Virzi Tone Producer.” The Tone Producer is a thin wide-grain spruce disc, .090″ thick, that is suspended inside the instrument and attached with two feet to the bass bar (soundboard) on violins, violas, bass viols, and similar instruments. The Tone Producer enhances the overtone series and adds richness and fullness to the instrument. (With a mandolin’s, guitar’s, and mandola’s quick attack-and- decay of sound production, the Tone Producer sacrifices some of the instrument’s amplitude. The reduction of amplitude is not as evident on violins due to the continuous energy production of the violin’s bow.)

Loar’s personal viola was made by August Diehl (1852-1922) and Loar had it fitted with a Virzi Tone Producer. Loar wrote about the benefits of the Tone Producer in Virzi’s 1929 catalog.

Loar had a Virzi Tone Producer installed in his August Diehl viola and wrote an article about its benefits that appeared on one page of the Virzi catalog. As a result of his experience, Loar recognized the Tone Producer as a beneficial feature for Gibson’s line of mandolins, and many F-5s, H-5s, and L-5s as well as some F-4s and a few A-model instruments made by Gibson in the period of 1923-1925 boasted the Virzi Tone Producer as an accessory feature. (However, recognizing that the Tone Producer did rob a bit of amplitude, Gibson preferred to promote the Virzi Tone Producer as a “Tone Amplifier.”)

Some believe that it was Loar’s involvement with Virzi that led to his sudden departure from Gibson. Others believe it was his strong desire to get Gibson motivated to manufacture electric instruments. And some believe it was the company’s difficulty in making and selling Master Model instruments. After years of research and in-depth study of his personal documents, I cannot find any proof that any of these were the case. We do know through Loar’s correspondence that he did not enjoy working in business where “profit” was the gating issue. In The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar, I describe the management struggles that occurred in 1924 that posed an uncomfortable work environment. And, we know that Loar’s desire to venture into electric instruments would have been a major departure from Gibson’s 25-year tradition of building and marketing acoustic stringed instruments. Regardless of the reason, Loar was highly motivated and needed to move on. Loar left Gibson at the end of October, 1924 leaving in question who “tested and approved” and then signed the labels for the two dozen instruments that were finished in November and December of that year. Especially when Loar was living in Boston at the time.

Gibson’s 1925 Accessory Catalog was well into print production when Gibson decided to discontinue the Virzi Tone Producer as an accessory at the end of 1924. Rather than reprinting the catalog, the pages for the “Tone Amplifier” were stamped “CANCELLED”.

Loar’s tenure with Gibson ended in October 1924. This photograph of Loar with an early pre-truss rod F-4 mandolin was one of the last pictures of him that appeared in Gibson catalogs (from the 1923 “M” catalog).

It is interesting to note, however, that when Loar left Gibson at the end of 1924, the Virzi Tone Producer (that Gibson called a “Tone Amplifier”) was cancelled as an accessory to Gibson’s line. It was done so quickly that they didn’t want to wait to remove it from the next catalog printing; the word “CANCELLED” was rubber stamped across the Virzi Tone Amplifier page. But this didn’t end Gibson’s relationship with Virzi as some believe. In fact, in January of 1925, Gibson announced that it was the sole distributor for Virzi violins, violas, cellos and basses in the United States. And in the early 1930s, Gibson itself was manufacturing violins.

Julius Bellson, one of Gibson’s early employees who wrote a book in the early 1970s about Gibson history (and later became Gibson’s part-time historian when he retired from Gibson), once shared with me that Lloyd couldn’t get along with Gibson management, but aside from working under the stern General Manager Harry Ferris, I have no factual data to support this. In fact, Lloyd had an excellent business relationship and friendship with company executive Lewis Williams. Ted McCarty, Gibson’s president from 1948-1966 knew Loar (but never worked with him), and he said that Loar was a highly-motivated and demanding individual who would have been difficult for anyone to work with.

Regardless of the reasons or causes behind his departure, Loar’s mind was ablaze with creative ideas, including his desire to improve the amplitude and tonal qualities of instruments other than fretted stringed instruments. In October of 1924, after more than four years as a Gibson employee, and two decades as a performer on Gibson instruments, Lloyd Loar left Gibson to pursue other interests.

Post Gibson

At the end of 1924 Loar was hired by Walter Jacobs, of Walter Jacobs Publishing and moved to Boston to be editor in chief of Melody magazine. While at Jacobs, Loar continued to write columns for the company’s primary publication, Jacob’s Orchestra Monthly and The Cadenza.

In 1925, Lloyd Loar also began working as a design consultant for the Gulbranson Company of Chicago – a piano manufacturer – and applied for the position of Professor of Acoustics in the Music School at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois – a position he hoped would parallel his friend Karl Gehrken’s position at Oberlin.

By 1926, Loar began arranging music for Joe Nicomede’s publishing company, Nicomede Music Co. of Altoona, Pennsylvania. (Joe was a Gibson devotee and popular performer of the time.) Loar published about two dozen method books including three tenor banjo books, four volumes of orchestral violin “system” books, a violin method book, two tenor banjo folios, two method books for tenor banjo bands, a U.S. Army Band March music book, and arrangements for the Overture Orpheus and the Lustspiel Overture, and more.

It was during the period of 1925-1943 that Loar focused diligently on amplification systems and keyboard actions. Loar’s interest in structural tuning branched over to pianos, and on December 24, 1928, he filed for a patent for tuned tone bars on a piano soundboard. This was to be the first of his 15 U.S. Patents. However, the Great Depression (1929 – ca. 1934) was just around the corner, and his patent, U.S. Patent 1,798,212 was not granted until March 31, 1931. In 1929, when the stock market crashed, Loar’s work at Gulbranson ground to a halt. As by some stroke of very good luck, he was hired as a professor at Northwestern University and was very fortunate to have an income at a time when employment was very scarce. (Historically, it is interesting to note that in times of recession, the music industry has experienced short falls and generally has been affected, but not fully decimated.)

Vivi-Tone and Acousti-Lectric

Lewis Williams and Lloyd Loar spent a lot of time on this wall outside Loar’s home in Rogers Park (a suburb of Chicato) planning and discussing the formation of ViVi-Tone.s

On November 1, 1933, Loar and close friend Lewis Williams, a former Gibson executive (in fact, the one who hired Loar into Gibson) and five other local businessmen founded the ViVi-Tone Company in Kalamazoo, Michigan for the purpose of the “manufacture and sale of wholesale and retail musical instruments, acoustic and electric products, including research, consulting services and financing such business.” This was a broad-based business plan that allowed Williams and Loar to venture into virtually any aspect of the music industry. The ViVi-Tone product line was very aggressive and included: mandolins, mandolas, mando-cellos, mando-basses, violins, violas, violin- cellos, double basses, ViVi-Tone Claviers, and Spanish, Hawaiian, tenor, and plectrum guitars. Many of these instruments were amplified employing Loar’s coil-wound pickup design. ViVi-Tone acoustic guitars were unusual in that both the soundboard and the backboard were made of spruce joined on the edges by a thick laminated rim. The company was very prolific, and design features changed so fast at ViVi-Tone that many instruments of the same model were found with different features.

On January 23, 1934, three months after the formation of ViVi-Tone, Loar, Moon, and Williams pursued a second round of financing. To accomplish this, they founded the Acousti-Lectric Company, also in Kalamazoo, as a holding company for ViVi-Tone. The new company had an identical charter to that of ViVi-Tone, with a goal of raising an additional $33,000 (over $730,000 in today’s economy) from the same seven stockholders that formed ViVi-Tone. No information is available regarding their ability to raise the full amount of the offering. In February of 1936, ViVI-Tone moved its headquarters to 6330 Gratoit Avenue in Detroit, with Loar spending most of his time working out of his home at 1321 Fargo Avenue in Chicago. Photos of Loar’s personal ViVi-Tone clavier, an electric full-keyboard instrument that used tuned reeds (round vibrating bars) instead of strings, can be found in my book The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar.

Loar developed numerous keyboard instruments and was awarded several patents for keyboard actions, amplification systems, string plucking systems, and attack (sound-producing) systems. These inventions included the ViVi- Tone Clavier a piano-like instrument that was electrically amplified, and featured tuned “reeds” or “chimes” producing a bell-like quality unlike any instrument preceding it. Each of the reeds was individually tuned to the correct frequency, and the reeds were struck by small felt-covered mallets activated by a normal keyboard action. The reeds were in close proximity to unique coil-wound electric pickups that led off to an amplifier. Unfortunately, the amplification systems of the day hummed and were noisy with static, and were poor by comparison to the pure tones of an un-amplified instrument. As a result, the noisy ViVi-Tone Clavier did not win the favor of musicians who tried them. Regardless, Loar was way ahead of the competition with his development of electric keyboard instruments in the mid-1930s.

The ViVi-Tone instruments were a major departure from acoustic stringed instruments of the time and featured soundholes on both the soundboard and backboard. The electrically- amplified instruments boasted Loar’s patented bridge-pickup system.

This is Loar’s personal ViVi-Tone Clavier. The speaker cabinet is to the immediate right of the Clavier. The small shelf on the bottom right of the Clavier is for the amplifier. This instrument is now at the National Music Museum at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, South Dakota

While many schools and performers wanted to try the ViVi-Tone Clavier, few wanted to buy one. These included artists like Percy Grainger and institutions such as the Dushkin School of Music (Winnetka, Illinois), Sherwood Music School (Chicago, Illinois), University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin), and the Central Washington College of Education (Ellensburg, Washington).

Loar’s correspondence files are filled with rejection letters.

For those organizations that purchased or tried the instruments, there were concerns about the inconsistent keyboard action in all keys, a “hum” in the amplifier, and differences in tonal qualities at various ends of the musical spectrum. Loar was called upon to make numerous service trips to solve these various problems, and many of these institutions were far away in light of the means of travel of the time. (One can only imagine that the traveling and frustration Loar experienced managing these service complaints was very draining.)

There is little doubt that Loar was highly motivated with interests at many levels, but all centered around music. His wife Bertha once reflected that “… Lloyd was very driven and couldn’t sit still.” Looking back on his accomplishments, it is clear that Loar’s Type A personality always had him working on more than one project at a time.

In addition to assigning several of his patents to Acousti-Lectric Company (the parent company for ViVi-Tone he and Lewis Williams founded in Kalamazoo), he also licensed his string-plucking patents to Frank Holton & Company of Elkhorn, Wisconsin who began producing a line of portable, amplified, harpsichord-like instruments.

For more detailed information on Loar and the development of ViVi-Tone read The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar.

Professor Loar

During the remaining years of his life, Lloyd continued to teach at Northwestern University where he met his second wife Bertha Snyder, a student in his Physics of Music class. While Loar taught three different courses during his 13-year tenure at Northwestern, only this class focused specifically on musical acoustics. Northwestern’s 1943 summer session catalog listed this class as:

C25. The Physics of Music (4). The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. 2:30-3:30. Mr. Loar. Fisk 315.

Mr and Mrs Lloyd Loar on their wedding day.

One of the wonderful pieces of memorabilia that Bertha kept through the years was a class notebook prepared by a student in Professor Loar’s last Physics of Music class he taught. In addition to the course description previously mentioned, Loar touched on the importance of tuned air chambers, bodies, and apertures, and he voiced his dislike for the tonal qualities of members of the “lute family” – which includes guitars and mandolins; the very instruments Loar worked so diligently to advance while at Gibson. The class began on Wednesday, June 23, 1943 but Lecture 12 was never given as Loar became ill and died six weeks later. (In the fall of 2007, I transcribed this notebook verbatim and scanned all of the original illustrations. The Physics of Music class notebook is now published and available directly from us here.)

Loar’s work even reached the pages of Webster’s Dictionary. Over a period of many years, Loar was a “sub-consultant” to his friend and mentor, Karl Gehrkens, the author of a book entitled The Fundamentals of Music. Gehrkens was a professor at Oberlin College who was also G.&C. Merriam’s Special Editor for Music during that time. (Merriam is the publisher of Webster’s Dictionary.) Loar helped with the technical definitions of various musical devices and acoustical systems and his rich correspondence to Gehrkens clearly indicates the depth of Loar’s understanding of musical science and how the piano key action works.

Tap tuning

If one had to sum up and highlight Loar’s most significant and enduring contributions to acoustic instruments, it would have to be in the area of structural “tuning.” This art of tuning was not merely adjusting the strings to the correct notes but rather tuning the various structural components of the instrument to specific pitches so that the whole instrument, working as a coupled system (acoustically speaking), produced the best tones possible from each of its parts. To accomplish this, soundboards, backboards, tone bars, f-holes, and air chamber sizes were adjusted so that each element was tuned to a specific note. In tap tuning, the parts are struck with a soft hammer to determine the frequency they produce. Wood is then remove (which lowers the pitch) until the desired pitch is reached. With the entire instrument assembled and tuned a quarter-tone off of concert pitch, and strings tuned to the concert pitch, the parts of the instrument responded harmonically rather than discordantly to the strings’ energy. The quarter-tone tuning suppressed any unwanted “beats” or overtones thus bringing forth the best dynamics and tonal qualities of the instrument. (For detailed information on tap tuning, read The Art of Tap Tuning by Roger Siminoff).

Loar did not create tap tuning as some suggest. Rather, he studied the tap tuning process employed by the early violin makers. He sought to bring it and other attributes of the violin to the non-bowed stringed musical instruments at Gibson and later to the string instruments he created for ViVi-Tone.

Although Loar’s achievements gained him great fame in the area of musical acoustics, he is little known for his great contribution to electric instruments, specifically the coil-wound pickup. His earliest instrument that featured this pickup was a solidbody viola that he built ten years before the introduction of solidbody electric guitars. This same patent depicts a pedal device with volume controls and an on-off switch. While Lloyd strove to achieve power and amplitude in the instruments he designed, he also appreciated the frustrations of being heard as an acoustic performer. As a result, he installed a pickup on his personal F-5 mandolin and developed a simple “effects pedal” – likely the first of its kind – to control the amplifier and the speaker’s mechanical vibrato system. Of special interest is that the pickup he installed on his mandolin sensed the movement of the strings through the pickup’s field rather than having the bridge resting on the pickup’s armature as in his ViVi-Tone instruments.

World War II approaches

In the late 1930s, on the heels of the Great Depression and in light of the deepening political unrest in Europe, Loar and millions of Americans entered a difficult financial period. While music was still an important interest and occupation in bad times, the unusual features of the ViVi-Tone instruments were not as quickly adopted as Loar and Williams had hoped, and the product line did not win the favor and support of serious musicians – a critical component that could have made their company thrive. Business slowed to a standstill, and by 1938, Loar was relying primarily on his income from teaching (a $400 stipend) and writing.

After the ViVi-Tone years, and during the time leading up to his death, Loar worked as a consultant for Frank Holton. Loar bore the responsibility of both designer and investment relations manager, attempting to garner funds from such famed piano manufacturers as Rudolph Wurlitzer (where Loar met Ted McCarty) and W. W. Kimball. But the timing was bad and the uncertainty of world economics and political unrest led to a lack of funding.

In 1939, Frank Holton decided to sell his piano and harpsichord manufacturing business, and Loar worked diligently to help him find a buyer. Loar’s correspondence file (about 150 documents and drawings) is filled with “sorry, we’re not interested” letters, but Loar appears to have plodded on with this endeavor through mid-1940.

Loar’s efforts in marketing the ViVi-Tone and Holton line of electric keyboard instruments and in finding investors to help continue research and development were not bearing fruit. Several manufacturers turned him down based on the uncertainty of the issues related to World War II and during a period of industrial crisis where all efforts and attention were turned to manufacturing war goods. With Lloyd’s business failing, Bertha remembers Lloyd being reserved and sullen in his later years. “Even his enjoyment for a good cigar dwindled,” she recalled. ViVi-Tone ceased operations in 1939, and the Holton Company was finally sold to Wurlitzer.

Loar’s passing

On September 14, 1943, at age 57 Lloyd Allayre Loar passed away while at his home with his wife Bertha at his side.

Unexpected discoveries

Loar’s instruments remained in storage in Chicago until Bertha and her second husband Ralph Westerberg moved to California in the early 1950s and had the crates shipped and moved to a storage facility near Los Angeles.

In February of 1994, my son, Mark, who lived near Bertha and occasionally helped Bertha with changing light bulbs and various household chores, moved the crates (with Bertha’s approval) from storage to Bertha’s garage. On March 13, 1994, I had the wonderful opportunity of opening these crates to photograph and document Loar’s instruments I don’t know the experience of making a discovery during an archeological dig, but the adrenalin rush I felt when extracting every nail from the crates, carefully removing the packing paper, and removing each instrument with the most delicate care is one I will never forget.

Final thoughts

Lloyd Loar’s contributions to acoustic and electric string musical instruments continue to go unrecognized by many. For the holders of Loar-signed instruments, his work lives on in the voice of the instruments they cherish. For many performers who are not fortunate to own a Loar-signed instrument, the hope of playing a “Loar” is ever present. And, for luthiers who follow the art of mandolin construction, there is nothing so pervasive as the goal of capturing that magical appearance and tone of a Loar-signed instrument from the Gibson/Loar era.

From studying the depth of his work, one gets the sense that in his eyes, the thing we hold so dear – the “Loar-signed mandolin” – was just an insignificant blip in his massive outpouring of creativity. Loar’s patents, letters, and drawings reveal a highly motivated individual with a thought process that never stopped – always searching for what lay beyond truth and excellence in musical instruments. Sadly, he could only share 57 years of his insights and creativity with us.

Much of Loar’s original music has been lost forever, but the memories of his work will endure in the instruments that bear his signature, in the hearts of those of us who admire and respect his contributions, in the photographs and documents in The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar, and in this web site, as long as these bits and bytes shall live.

====

For further reading: The life and work of Lloyd Allayre Loar, 8-1/2˝x11˝, 200 pages, 320+ photos. www.siminoffbooks.com.