The Gibson factory at 225 Parsons Street, Kalamazoo, Michigan, ca:1940. Heralding a 48-star American flag, and getting into full swing before the War years, Gibson’s signage (on both the left and right face of the building) boasts “guitars, banjos, mandolins, violins, music, and strings.” Banjo and mandolin production continued in this facility, kindly referred to by Gibson employees as “the old building,” until Gibson moved its operations to Nashville in 1984. The building still stands, today. (The photo, originally black and white, has been color enhanced for this web page.)

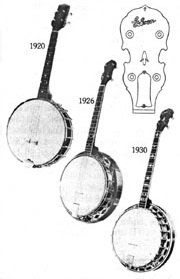

Several events and model announcements occurred during a period I refer to as “the 20 Golden Years,” developments that have been documented by factory records, historical papers, early catalogs, and dated price lists:

1918: The first announcement of a Gibson banjo appeared in October of that year. It was listed as a TB (tenor banjo) with no style number designation. No other members of the banjo family were listed. Lloyd Loar joins Gibson.

1919: A price list issued in September 1919 indicated that five banjo models were available: TB, GB (guitar banjo), MB (mandolin banjo), and CB (cello banjo).

1920: The first announcement of a style-2 designation appeared in a November 1920 listing, an option available only for the MB and TB models.

1921: No change in model designations.

1922: All banjos sold in 1922 were supplied with a Tone Projector (resonator-like backing), armrest, and finger-rest. Style-2 was still only available on MB and TB models. Gibson was granted U.S. Patent No 1,402,876 on January 10, 1922, for a banjo rim and neck attachment design.

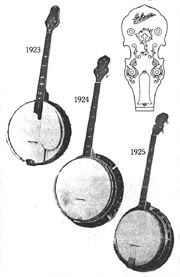

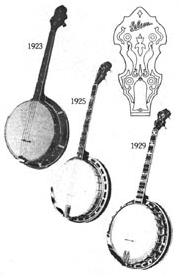

1923: The styles -Jr., -3, -4, and -5 were added to the line in May 1923. The CB and GB were only available in style -4, and the MB was not available in style -1 or style -5.

1924: The plectrum banjo (PB) and the regular banjo (RB, 5-string) were added to the line in January 1924, and only available in styles -Jr., -3 and -4. In December of that year, the UB (ukulele banjo) was added to the line in one version only (no style number).

1925: The full-resonator (with back and sides), spring-loaded ball bearing tone chamber was announced in February 1925. The first announcement of the Mastertone name as a style designation appeared in the July 1925 price list (prior to that time, the name was used in catalogs as a product title). The style -0 was made available for MB and TB models. The first announcement of the Granada appeared in this year. The style -Jr. was deleted from the listings (replaced by the style -0). this year also brought the first indication of diamond-shaped openings in resonator plates. The UB (ukulele banjo) style 1 was designated as having a 6″ rim and the styles UB-2 and UB-3 were designated as having an 8″ rim, and all other banjos (except for the 14″ CBs) were to have 11″ rims only (previously, some models had 10-1/2″ rims).

1926: A February 1926 listing showed that plectrum banjos (PB) were also made available in styles -1, Granada, and -5.

1927: The Bella Voce and Florentine models were added to the line in August 1927. UB models were available in styles -1 through -5.

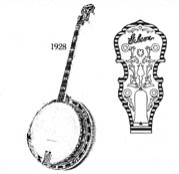

1928: The style -6 was added to the line in September 1928, available in TB and PB models only. with the exception of the UB-5, the style -5 banjo was dropped from the line. Gibson received U.S. Patent No. 1,678,456 on July 24, 1928 for its design of the spring-loaded ball-bearing tone chamber.

1929: The style PT was announced in May 1929. This instrument had gold-speckled binding, “Argentine grey” finish (actually a yellow-orange), and a string scale halfway between that of a plectrum and tenor. The one-piece flange, low profile flattop tone chamber, and double cut peghead were also announced this year.

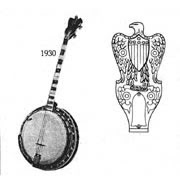

1930: The style -5 was dropped from the UB models. The bass banjo (BB) was announced. The Bella Voce was dropped from the line, and the All American model was introduced. The PT was also deleted from the line.

1931: Style -11 was introduced in November 1931. Style -0 was discontinued.

1932: No changes or deletions.

1933: Bass banjo dropped from the line.

1934: No changes or deletions.

1935. The style -00 was added to the line in February 1935 and made available on TB, PB, RB, and MB models.

1936: No changes or deletions.

1937: The style-75, and top-tension models -7, -12, and -18 were added to the line in August 1937. They were available in TB, PB, and RB models only. Styles -2, -3, -4, -6, and Granada, All American, and Florentine were dropped from the line.

1938: The UB was available for the last time, in style -1 only.

Note: Some exceptions to deleted models appearing with later serial numbers did occur as part of custom orders for important customers or resellers.

Gibson’s banjo models featured a robust series of changes in the design and implementation of tone-chambers, rims, flanges, resonator designs, platings, woods, bindings, marquetry, inlay, hardware, engravings, and finishes.

Most all of the Gibson banjos were available in tenor banjo (TB), plectrum banjo (PB), guitar banjo (GB), mandolin banjo (MB), ukulele banjo (UB), and regular (5-string) banjo (RB) models. A few were available in a half-breed plectrum/tenor (PT) whose string scale was halfway between plectrum and tenor.

The following is a brief description of the changes made during Gibson’s 1918-1938 Golden Year era.

All American

A richly- decorated banjo model with a carved and colored eagle on the resonator back, and a three-dimensional eagle carved on the peghead. The fretboard was hand-painted with scenes depicting the development of American history. Gold-plated engraved hardware, pearloid fretboard, burl walnut and white holly woods.

Florentine

An elaborate instrument boasting Italian Renaissance motifs. The pearloid fretboard was hand painted with multi-colored scenes and the resonator back was carved and colored with a fancy crown-and-crest design. The peghead was veneered in pearloid, inlaid and bordered in colorful rhinestones. The hardware was gold-plated and richly engraved. Available in burl walnut, curly maple, Brazilian rosewood, or white holly woods. (Some had white-painted maple.)

Bella Voce

Similar to the Florentine model, except the Bella Voce featured a rosewood fretboard with mother-of-pearl inlays, and a lyre design carved and painted on the resonator back. The first models had an ebony-veneered peghead with two variations of elaborate mother-of-pearl inlays, later changed to the same peghead as the Florentine model. “fiddle” headstock.

Granada

The very first Granada model had a curly maple neck and resonator, with gold-plated, engraved, and burnished (dulled) hardware. The fretboards were Brazilian rosewood and the instrument was inlaid in the “hearts and flowers” design. The inlay pattern was changed to the “eagles” design when the “double-cut” headstock was introduced.

Style -75

This model was the top-of-the-line of the standard models during the latter part of the 20 Golden Years (other than the higher numbered top-tension models). It was constructed of Honduras mahogany, with a rosewood fretboard and rather plain inlay designs. The headstock was inlaid in a fancy, but not overly decorative motif; and the hardware was nickel plated.

Style -18

The best of the top-tension models. this instrument featured an arched (radiused) rosewood fretboard, large art-deco inlays, a new art-deco peghead design bound in white/black/white, and a carved (rather than laminated) heavy resonator whose outer surface was turtle-shell shaped. The top-tension model was the first official announcement of the flattop tone chamber design (although it was previously available on special order). Hardware was gold-plated and engraved, and the neck and resonator wood was curly maple. The resonator on top-tension models was machine carved from a solid piece of wood, instead of being laminated as on other models. The extra bulk, of hardware, plus the solid resonator made this model the heaviest of the Gibson banjo line (which served to provide great power). Tuning pegs had a large squarish housing which reflected the designs of the art-deco period.

Style -12

The middle of the top-tension models. Virtually the same as the style -18 except the style 12 was chrome plated, not engraved, and featured black walnut as a neck and resonator wood. The instrument was finished in a dark sunburst with dark regions around the outside back of the resonator, at the neck heel, and at the back of the peghead. Most of the top-tension models had three-digit serial numbers.

Style -11

A lower-priced standard model with pearloid fretboard, peghead, and resonator back all of which were silk screened in a multi-colored floral motif. Hardware was nickel-plated. This model had a 1/4″ brass rod as a “tone chamber” rather than the cast tone on better models. Some versions had necks that were painted royal blue.

Style -7

The bottom of the top-tension line. This style was made of plain maple and finished in dark brown. The hardware was nickel-plated and the inlay design was similar to the “bowtie” pattern used in the style -250 banjos of the late ’50s (although the style-7 had several slots cut into the sides of each inlay piece).

Style -6

This banjo was a handsome combination of curly maple woods and flashy binding. The first models boasted black and white checkerboard-like binding. A variation of the style was introduced as the PT, an instrument with gold-speckled binding and a string scale length halfway between that of tenor and plectrum. After the PT’s short tenure (two years of production), several style-6 banjos were made with the same gold-speckled binding. The style -6 had hearts and flowers inlays, rosewood (later ebony) fretboards, gold-plated and engraved hardware, and a yellow-orange finish called “Argentine Grey.”

Style -5

The style -5 was available in two distinct models. First as one of the early “trap-door” and Pyralin resonator banjos. The tone chamber at that time was the plain ball-bearing type. Fretboard inlay pattern was a fancy floral pattern, and the hardware was gold-plated. In 1925 with the introduction of the spring-loaded ball-bearing tone chamber, this style was introduced with a full resonator, “wreath” inlay design, gold-plated and engraved hardware, figured walnut neck and resonator wood, ivroid binding, wood-inlay marquetry on the back of the peghead, and fancy purfling.

Style -4

This style was the top of the standard (not engraved, carved, or gold-plated) line. The first version, introduced in 1923, featured silver plating, ebony fretboard with pearl dots, curly maple neck wood, and Pyralin resonator. In 1925 it featured a Honduras mahogany neck and resonator, nickel-plated hardware, Brazilian rosewood fretboard, hearts-and-flowers inlay design, and white/black/white binding. In 1929, the style -4 was changed to the same “eagles” inlay pattern as the Granada of that period. The wood was changed to burl walnut, and the plating changed to chrome.

Style -3

The first style -3 was introduced in 1923 and boasted nickel plating, an ebony fretboard with dot inlays, and plain maple neck wood. In 1925 the style -3 featured “snowflake” inlays, nickel plating, plain maple neck and resonator wood, and was finished in a dark-reddish brown mahogany color. In 1929, the inlay was changed to large, fancy designs. In 1937, a variation of this style became the style -75 (see above).

Style -2

The 1920 version had dot inlays, an ebony fretboard, and no resonator. In 1925 it featured a full resonator, shoes with a wavy-shaped flange, simple inlay designs, rosewood fretboard, and an amber-brown finish. In 1926, the openings in the flange were changed to diamond-shaped. The versions after 1930 had one-piece flanges, silk screened decorations, walnut resonators, and pearloid fretboards.

Style -1

This banjo was introduced in 1922 with nickel plating, an ebony fretboard with pearl dots, and a “trap door” resonator. In 1925 the fretboard was changed to rosewood with fancy inlay shapes, the resonator was deleted, and a 10-1/2″ head was featured. In 1926, the style changed to a full-resonator model with shoes-and-plate flange and an 11″ head. In 1930 it further changed to a dark mahogany (stain over maple) finish, and “bat” inlays, In 1936 the inlay pattern changed again to simple dots.

Style -0

The style -0 was introduced in 1925 with an “ebonized maple” fretboard, dot inlays, no resonator, and a 10-1/2″ head. In 1926 it was changed to an 11″ head. The finish during both years as an antique mahogany stain over maple.

Style -00

This was the bottom of the line when it was introduced in 1935, it was made with a rosewood fretboard, dot inlays, nickel plating, white binding, and plain maple wood finished in a light walnut stain. This instrument had a round rod (rather than cast) tone chamber and a one-piece cast flange.

The Gibson Mastertone banjo is one of those great success stories; and though it had its occasional failures, the “Mastertone” brand has made it through more than 75 years of hard times and rough service. Today, it is the only surviving representative — still in production — of the turn-of-the-century banjo era; and it is the instrument most highly acclaimed by both bluegrass and dixieland banjoists. While several models were unsuccessful, a major portion of the line won its way to the stages, homes, and hearts of countless musicians.

The Gibson Mastertone has been copied by private luthiers and commercial manufacturers alike. Certain models bring the highest prices from collectors around the world, and for some professional bluegrass banjoists, a Mastertone is the only instrument they will play. For others, the image is so strong that they feel that they are not really rendering a certain music style unless they are doing so on a “Gibson.”

Although several evolutionary design changes were made, the instrument has remained basically the same from about 1938 until 1985. In that year, I worked closely with Gibson and Earl Scruggs to bring back the design styles of the early years — a project which was the foundation of the Earl Scruggs model banjos now produced by Gibson.

The most interesting part of the Gibson banjo history transpired between its inception in October 1918, and a time around 1938 (see Chronology of Gibson Banjos) when, in my opinion, the line went through its greatest evolution. While there were several new model introductions after that period (such as the styles -100, -250, and -800), there is a wonderful story in changes made during those first 20 Golden Years.

At some point in 1917, the company began to work on a simple open-back banjo. The first banjo was announced in a price list dated October 1918. It was a plain tenor model, simply promoted as a “tenor banjo.”

The period of 1918 to 1924 marked a very important era for Gibson. It was a time of greater sensitivity that the company had known before: A time when the likes of such renowned luthierie figures as Lloyd A. Loar, Guy Hart, George D. Laurien, and Lewis A. Williams graced the halls and workbenches at the Gibson Plant in Kalamazoo; a time when great men were forming great ideas; a time when Gibson was to win honor with its finest instruments — the style-5 Master series. These included the Master Model Mandolins (F-5’s), Master Model Mandolas (H-5’s), Master Model Guitars (L-5’s), and the Master Model tenor banjos (TB-5’s) (from which the “Mastertone” name was derived).

Gibson banjos changed drastically during their early stages of development. The first resonators were flat, plate-like discs that covered the back of the pot assembly (body) with half the plate hinged to swing out like a trapdoor. Loar had his hand in developing a floating tone tube with 20 ball-bearing contact points, and a “tuned air chamber.” This was followed by a bolt-on celluloid (Gibson called it “Pyralin”) plate. Finally, in February of 1925, the company announced an all-new banjo. The first had a spring-loaded tone chamber and a full wooden resonator. Variations which grew from this model were to become the standard of excellence for banjos around the world.

The craftsmanship of the earliest Gibson banjos was good, but the construction was nothing more than basic. The first laminated rims had a cavity between the laminates in the upper portion to act as a “tone chamber,” but the head rested directly on rim rendering the tone chamber virtually useless.

Gibson made great strides with one problem that plagued most banjo makers. Of all instruments in the line, the banjo had the longest and thinnest neck and other makers went through great strides to laminate and fortify the neck to prevent it from warping under string tension. Gibson’s Thaddeus McHugh invented an adjustable truss rod in 1921 that kept Gibson necks straight. Interestingly, however, the patent called for the rod to be installed being lowest in the heel and peghead, with the center of the rod close to the fretboard. While this provided “post tensioning” and kept the necks straight, over-tightening of the truss rod nut would cause the neck to bow backwards. It wasn’t until many years later that Gibson inverted the rod’s curve (with the center of the rod being positioned away from the fretboard inside the neck).

Following are details on models and construction features during this period:

Model designations: The banjo models were given letter codings to indicate the type of stringing: “TB” referred to a tenor banjo, “PB” stood for plectrum banjo, “GB” described a guitar banjo, “MB” was applied to a mandolin banjo, “UB” denoted a ukulele banjo, and “RB” indicated a regular (5-string) banjo. The letters were followed by a number indicating the grade or quality of the instrument: -00 (double zero) was bottom of the line (although there was a short-lived “Jr.” model which was the least expensive); -0 was next; -1 was slightly better, and usually meant nickel plating and plain-colored finish; -11 (double 1) was a later inexpensive version; -2 followed with fancier inlays and extra binding; -3 was fancier; -4 fancier yet; and -5 (for a brief period) was the fanciest model boasting gold plating, choice curly maple, and elaborate inlay designs. Thus a TB-5 was a tenor banjo with -5 grade fancy trimmings. (For more detailed information on the various models, see Banjo Models.)

From 1925 to 1930, several fancy models made their debut; the style -6 with fancy black-and-white binding (or sometimes gold-speckled binding); the TF or Florentine; the TG or Granada; the Bella Voce (which means “beautiful voice” in Italian); and the All American — an elaborate instrument with a carved eagle on the peghead.

Rims: Except for the very first Gibson banjos, all of the rims for this period have been made of steamed, rolled, and laminated maple. Depending on the model, there were constructed of either three or four plies: three plies of 1/4″ maple to make up a 3/4″ rim machined down for one-piece flange models, and four plies of 1/4″ rim to make up the heavy rim used for tube-and-plate models. All of the laminates were taper-cut, a method of angling the joining ends of each laminate so that they would overlap rather than have a flat end-to-end joint.

To the inexperienced observer, some rims appear to have been made of five thinner plies; but this is a misconception caused by a practice still in use today. The bending and lamination process is a difficult one and several rims might come off the mold with unsightly glue joints. To improve the cosmetic appearance, a poorly glued three-ply rim would be placed on a lathe and a “cut” made into the glue joints. Then, thin filler strips would be glued into the cuts and then machined flush, resulting in a multiply appearance, while still basically a solid three-ply construction.

One-piece flange models required that the rim be machined down so that the flange could slip over the rim, and thus the rim had thin walls approx 1/2″ thick. The tube-and-plate models required an added lip to support the tube and did not require machining down of the rim, leaving the tube and plate rims to be a full 3/4″ thick.

Flanges: The tube was the first non-shoe system used by Gibson to secure the tension hooks (that tighten the head). As with later models, the tube was secured against a lip on the rim. By acting as a tight band around the rim, the tube also added greater structural integrity than competing bracket and shoe models. At the first introduction of the full resonator models, a stamped “plate” was added beneath the tube to fill the opening between the rim and the lip of the resonator. This plate had stamped perforations around its surface. At one point, the lesser models had hex-shaped “diamond” openings in the flange compared to the classic Mastertone crescent/arch opening with rounded ends. To secure the pot assembly to the resonator, the earliest models used small hex-head screws that went through a hole the flange to a lug in the resonator. This was later changed to the same hex-head screw going through a separate bracket below the plate that was attached to the rim, and still later to a serrated thumbscrew replacing the hex-head screw.

Coordinator rods: One of Gibson’s long lasting developments for attaching the neck to the rim was the “coordinator rod” system; two brass rods that attached to two screws in the heel of the banjo neck. The rods secured the neck to the rim and provided a means for correcting the “action” (height of strings above the fretboard). By selectively tightening the nuts at the tailpiece-end of the rods, the angle of the neck could be changed to adjust the neck’s angle. Gibson’s first banjos had a nut on the top neck screw and only one rod on the lower neck screw. The earliest banjos with the double-rod coordinator rod sytem had one lag screw threaded into the neck and one “L”-shaped lag screw embedded into the bottom of the neck’s heel (these lower screws are permanently glued in and can not be removed). (Banjos with embedded lower screws also had an separate heel cap (wooden piece) covering the bottom of the neck heel.)

Tone chambers: The “tone chamber” was a cast ring that sat on top of the wood rim to add rigidity and mass to the “pot assembly” (banjo’s body) and enhance the vibrations of the (then) skin head. Several variations were created by Gibson, and these can be followed in my web page on the Evolution of Gibson Banjo Rims. It has been thought that the spring-loaded “ball bearing” tone chamber was designed to counter the effects of weather changes on the skin heads. This is not true, especially since any vertical change in the head’s position would cause improper playing action. The springs were employed to improve the resilience (springiness) of the tone chamber. The ball bearing tone chamber design is attributed to Lloyd Loar.

Woods: Each of the model designations indicated a particular species of wood used for that model (see Banjo Model Features, below). The lower numbers indicated that plain maple was used with a colored finish such as “dark mahogany” stain used over maple. Curly maple, burl walnut, and Honduras mahogany were available on their respective models. Other woods such as white holly, were available on fancy models like the Florentine and Bella Voce. In all cases, the rims were made of maple, and the majority of fretboards were made of Brazilian rosewood (not ebony as commonly believed). Only the pre-1925 (trapdoor period) and style -6 banjos had ebony fretboards. Except for the earliest models, all of the banjos made from 1925 to 1935 (in fact, until around 1969) had one-piece necks (however, pegheads were fitted with laminated “ears” to give them the necessary width, and the earliest models had a veneer over the back of the peghead to cover up the ear’s glue joints).

Banjo serial numbers: During the 1920s, Gibson instruments were made in lots of 40s (for the most part, this procedure continues today). The bins that were used to move instruments from department to department had 40 cubbyholes. An entire bin was a “lot” and would contain instruments of the same model. Sometimes, two or three bins or lots of the same model would be made at one time. To assure that parts would fit together and that the finish color would match, the serial number of each banjo was stamped inside its rim, penciled on the neck heel, and chalked or painted in white or red on the inside surface of the resonator (with red numbers most often being painted along the inner edge of the resonator so they could be read through the holes in the plate or flange, yet the red would not be obvious from a distance).

The number was in two parts: first a four-digit number to indicate the factory order number or lot number, and then a second series (usually two digits) to designate that particular banjo within the lot. Banjos made prior to February 1925 were numbered in the 11,000s. With the introduction of the new full-resonator models in February 1925, a new prefix was assigned to the banjo line, beginning with 8,000. Around 1935, when the series reached the 9,900s, it was again changed to a whole variety of numbers whose dates have been difficult to document or verify. Although each new year did not precisely mark a change in the numbering system, the following chart will serve as a close guide to Gibson’s early serial numbers (for banjos) and their approximate date:

1925…..#8,000

1926…..#8,350

1927…..#8,600

1928…..#8,800

1929…..#9,000

1930…..#9,200

1931…..#9,400

1932…..#9,600

1933…..#9,700

1934…..#9,800

1935…..#9,900

1936…..various

Platings: Instruments were offered in three basic plating finishes; nickel, chrome (them called “chromium”), and gold. The gold plating was often referred to as “triple-gold plating” — a description of the length of time pieces were left in the plating bath (and not an indication that three separate plating processes were done). Some of the gold-plated models were “Florentined,” a burnishing technique that dulled the plated surface to produce a matte background.

Many interesting changes occurred in the development of the Gibson banjo line between its inception in October 1918, and the end of it’s “pre-war” era in 1938. (For a glimpse at the sequential development, see Chronology of Gibson Banjos.)

Following are details of construction features that occurred during this period:

Depending on the model, there were either of three or four plies: three plies of 1/4″ maple to make up a 3/4″ rim machined down for one-piece flange models, and four plies of 1/4″ rim to make up the heavy rim used for tube-and-plate models. All of the laminate ends were taper-cut, a method of angling the joining ends of each laminate so that they would overlap rather than joint flat end-to-end.

Model designations: The banjo models were given letter codings to indicate the type of stringing: TB referred to a tenor banjo, PB stood for plectrum banjo, GB described a guitar banjo, MB was applied to a mandolin banjo, UB denoted a ukulele banjo, and RB indicate a regular (5-string) banjo. The letters were followed by a number indicating the grade or quality of the instrument: -00 (double zero) was bottom of the line (although there was a short-lived “Jr.” model which was the least expensive); -0 was next; -1 was slightly better, and usually meant nickel plating and plain-colored finish; -11 (double 1) was a secondary inexpensive version; -2 followed with fancier inlays and extra binding; -3 was fancier; -4 fancier yet; and -5 (for a brief period) was the fanciest model boasting gold plating, choice curly maple, and elaborate inlay designs. Thus a TB-5 was a tenor banjo with -5 grade fancy trimmings.

From 1925 to 1930, several fancy modes made their debut; the style -6 with fancy black-and-white binding (or sometimes gold-speckled binding); the TF or Florentine; the TG or Granada; the Bella Voce (which means “beautiful voice” in Italian); and the All American — an elaborate instrument with a carved eagle on the peghead.

For detailed descriptions of banjo models, see Gibson Banjo Models

Rims: Except for the very first Gibson banjos, all of the rims for this period have been made of steamed, rolled, and laminated maple. Maple was selected for its superior bending qualities compared to other woods in it’s weight/mass class (cherry, oak, etc.) at approx 35-40 pounds per cubic foot.

The added mass of the fourth ply on tube-and plate rims contributed to the brightness and amplitude of these banjo models.

One-piece flange models required that the rim be machined down so that the flange could slip over the rim. This resulted in a 9-1/2″ inside diameter and approximately 10-1/4″ outside diameter, and thus the lower portion of the rim had thin walls approx 9/16″ thick. The tube-and-plate models required an added lip to support the tube and did not require machining down of the rim, leaving the tube and plate rims to be a full 3/4″ thick.

To the inexperienced observer, some rims appear to have been made of five thinner plies; but this is a misconception caused by a practice still in use today. The bending and lamination process is a difficult one and several rims might come off the mold with unsightly glue joints. To improve the cosmetic appearance, a poorly glued three-ply rim would be placed on a lathe and a “cut” made into the glue joints. Then, thin filler strips would be glued into the cuts and then machined flush, resulting in a multiply appearance, while still basically a three-ply construction.

Flanges: The tube was the first non-shoe system used by Gibson to secure the tension hooks (that tighten the head). At the first introduction of the full resonator models, a stamped “plate” was added beneath the tube to fill the opening between the rim and the lip of the resonator. This plate had stamped perforations around its surface. At one point, the lesser models had hex-shaped openings in the flange compared to the classic Mastertone arched opening with rounded ends. The first models used small hex-head screws that went through a hold the flange to hold the flange and rim assembly to the resonator. This was later changed to the hex-head screw going through a separate bracket below the flange that was attached to the rim, and still later to a serrated thumbscrew replacing the hex-head screw.

Coordinator rods: One of Gibson’s developments for attaching the neck to the rim was the “coordinator rod” system; two brass rods that attached to two screws in the heel of the banjo neck. The rods secured the neck to the rim and provided a means for correcting the “action” (height of strings above the fretboard). By selectively tightening the nuts at the tailpiece-end of the rods, the angle of the neck could be changed to adjust the neck’s angle. Gibson’s first banjos had a nut on the top neck screw and only one rod on the lower neck screw. The earliest banjos with the double-rod coordinator rod sytem had one lag screw threaded into the neck and one “L”-shaped lag screw embedded into the bottom of the neck’s heel (these were permanently glued in and could never be removed).

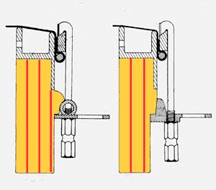

Tone chambers: The “tone chamber” was a metallic device that sat on top of the wood rim to enhance the vibrations of the (then) skin head. Several variations were created by Gibson, and these can be followed in the Evolution of Gibson Banjo Rim Assemblies. It has been thought that the spring loaded “ball bearing” tone chamber was designed to counter the effects of weather changes on the skin heads. This is not true, especially since a vertical change in the head’s position would cause improper playing. The springs were employed to improve the resilience (springiness) of the tone chamber. This design feature is attributed to Lloyd Loar.

Gibson’s spring-loaded ball-bearing tone chamber system was a marvelous engineering feat of wood and metal parts. The assembly included (left to right) a grooved stretcher band, exterior tone chamber rim, tone tube with integral lip and arched upper ring, tube and plate assembly, 24 ball bearings, 24 coil springs, and 48 flat washers.Each spring was rated at 460 pounds per inch.

Of the 48 washers, 24 were placed below the springs, and 24 were countersunk – to hold the ball and keep it centered – and placed above the washers. Each spring, washer, and ball assembly went into a hole drilled in the rim. To ensure accurate height and contact of the balls to the tone tube, thin paper shims were placed beneath the bottom-most washer and the rim. (The shims are often discarded and rarely found on banjos today, except on those rare banjos that were never disassembled before.)

With all the springs in place, the rim is finally ready to have the tone tube installed. The assembly of these rims was very time consuming and it is no wonder that the Company eventually favored a one-piece tone chamber and lastly, a one-piece cast flange.

The ball-bearing tone chamber was followed by its look alike (from the outside) cast one-piece arch-top tone chamber, and later by the wider active surface of the flat-top tone chamber.

Woods: Each of the model designations indicated a particular species of wood used for that model (see Banjo Model Features, below). The lower numbers indicated that plain maple was used with a colored finish such as “dark mahogany” stain used over maple. Curly maple, burl walnut, and Honduras mahogany were available on their respective models. Other woods such as white holly, were available on fancy models like the Florentine and Bella Voce. In all cases, the rims were made of maple, and the majority of fretboards were made of Brazilian rosewood — not ebony as commonly believed. Only the pre-1925 (trapdoor period) and style -6 banjos had ebony fretboards. Except for the earliest models, all of the banjos made from 1925 to 1935 (in fact, until around 1969) had one-piece necks (however, pegheads were fitted with laminated “ears” to give them the necessary width, and the earliest models had a veneer over the back of the peghead to cover up the ear glue joints).

Banjo serial numbers: During the 1920s, Gibson instruments were made in lots of 40s (for the most part, this procedure continues today). the bins that were used to move instruments from department to department had 40 cubbyholes. An entire bin was a “lot” and would contain instruments of the same model. Sometimes two or three bins or lots of the same model would be made at one time. To assure that parts would fit together and that the finish color would match, the serial number of each banjo was stamped inside its rim, penciled on the neck heel, and chalked or painted in white or red on the inside surface of the resonator (with red numbers most often being painted along the inner edge of the resonator so they could be read through the holes in the plate or flange, yet the red would not be obviously visible).

The number was in two parts: first a four digit number to indicate the factory order number or lot number, and then a second series (usually two digits) to designate that particular banjo within the lot. Banjos made prior to February 1925 were numbered in the 11,000s. With the introduction of the new full-resonator models in February 1925, a new prefix was assigned to the banjo line, beginning with 8,000. Around 1935, when the series reached the 9,900s, it was again changed to a whole variety of numbers whoe dates have been difficult to document or verify. Although each new year did not precisely mark a change in the numbering system, the following chart will serve as a close guide to Gibson’s early serial numbers and their approximate date:

1925…..#8,000

1926…..#8,350

1927…..#8,600

1928…..#8,800

1929…..#9,000

1930…..#9,200

1931…..#9,400

1932…..#9,600

1933…..#9,700

1934…..#9,800

1935…..#9,900

1936…..various

Platings: Instruments were offered in three basic plating finishes; nickel, chrome (them called “chromium”), and gold. The gold plating was often referred to as “triple-gold plating” — a description of the length of time pieces were left in the plating bath (and not an indication that three separate plating processes were done). Some of the gold-plated models were “Florentined,” a burnishing technique that dulled the plated surface to produce a matte background.

Banjo model features:

Several models graced the Gibson banjo line in this period. For detailed information see Banjo model features.

Gibson’s ball-bearing tone chamber

c:1925

Fig. 1

The very first Gibson banjo rim “pot” assemblies utilized shoes (A) that held onto the rim (B) with hex-head, screws (C), as shown in Fig 1. The top half of the outer edge of the hooks (D) were flattened and were designed to fit into a grooved stretcher band (E). The nuts (F) were large and had a rounded bottom. A simple round rod served as a tone ring (G), and rested on top of the rim. The skin heads were held on with “flesh hoops” (H), which were rings of either round or square brass. Necks were originally fitted to the rims with standard wooden “dowel sticks.” That system gave way to a combination of a dowel stick and a single coordinator rod, which in turn was replaced by an upper nut and a lower coordinator rod (a single rod was unable to “coordinate” the neck’s axis, and was later replaced by two coordinator rods (although some models in the late 50s and early 60s had only one rod).

Fig. 2

The first version of the ball bearing tone chamber design is shown in Fig 2. Holes were drilled (A) into the top of the rim, and steel washers (B) were inserted to keep the balls (C) centered (some early versions had steel discs instead of washers), and to prevent them from digging into the wood. The hollow tube (D) that rested on top of the 20 balls was drilled (E) around its inner circumference. The balls were intended to prevent the tube from resting directly on the rim with the intention of making the tube resilient (springy). These early ball bearing rims had a thicker rim section (F) beneath the shoes. These rims also had the rounded bracket nuts that required a 5/16″ nut wrench (the long, straight nuts on later models required a 1/4″ nut wrench).

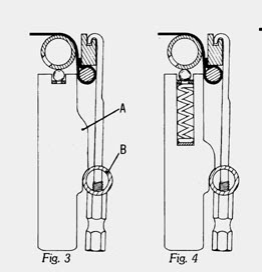

Fig. 3 & Fig. 4

Fig 3. Shortly after the introduction of the ball bearing system, a lip (A) was machined into the rim’s side to support the tube (B), which replaced the shoes. The tube added greater structural stability to the rim (acting as a hoop on a barrel) and assured that the laminates would not separate. The hooks were still the flat design, but the nuts (1/4″ hexagonal) were changed to a more elongated shape.

Fig 4 indicates the addition of springs beneath the ball bearings to further increase the resiliency. The outer profile of the rim’s lip was slightly changed to be more rounded and not as flat as (A) in Fig 3. As with the rims in Fig 3, the bracket nuts were the same elongated hexagonal 1/4″ nuts.

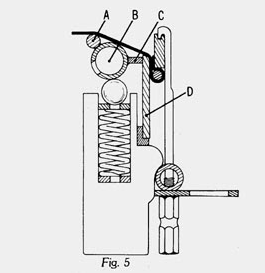

Fig. 5

A major design change occurred in 1925 with the introduction of the modified ball bearing tone chamber (Fig. 5). A round rod (A), smaller in both diameter and circumference, was brazed onto the hollow tone tube (B). A second stamping (C) was brazed to the outside diameter of the tone tube to keep it centered within the outer support ring (D). [The early support rings were drilled with a staggered-hole pattern, which is visible from the outside of the banjo at position (D)]. Flat hooks were still used on this version, and the springs were larger than on previous models. The banjo head had two contact points, giving it the first “arch top” profile. Lastly, we see the introduction of the hexagonal 1/4″ bracket nut which is still currently used on Gibson banjos.

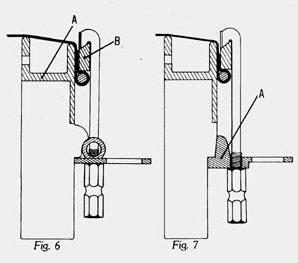

Fig. 6 & Fig. 7

In 1927, the first cast tone chamber (A) was employed (Fig. 6), which supported the head in the same arch-top manner as its predecessor. The inside perimeter of the tone chamber was drilled with 40 holes (although several instruments have been found with undrilled chambers). With the introduction of this system, a notched stretcher band (B) made its appearance, secured with round hooks that had straight-sided hexagonal nuts. The four-ply rim had a machined lip that accepted the tube. This design greatly simplified the banjo’s structure, which reduced manufacturing and assembly problems.

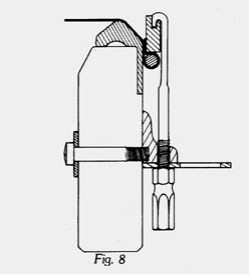

Fig. 8

The style-2 banjos of 1930 featured a small cast tone chamber of modified arch-top design, with flat hooks, a grooved stretcher band, and a full 3/4″-thick three-piece rim. And, as indicated in Fig. 8, the shoes were not entirely banished from Gibson’s line. Lower-numbered models employed shoes with four-sided “diamond-hole” flanges and flanges whose plates were stamped in a wavy, flowing pattern. While these rims were used on lesser models, they had substantial mass (because they could be used a full 3/4″ thick since no flange or tube had to slide up on, and be attached to the rim) and proved to be good sounding banjos.

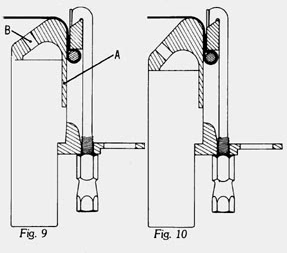

Fig. 9 & Fig. 10

Fig. 9. In the early ’30s, a new tone chamber was designed to take advantage of the full 11″ head diameter. A cast tone chamber was prepared with a .655″-high lip (A) that could fit in place of the arch-top tone chamber (which had a lip of the same height). This design is often referred to as the “low-profile flattop tone chamber.” It was drilled with 20 holes (B).

Around 1935, a new flattop tone chamber (Fig. 10) was designed with a top portion deeper than that of its predecessor. Because the “tone chamber” portion was larger, it only had a .420″ lip, and thus was not inter-changeable with the arch-top tone chambers. The flattop tone chamber was available as an option, but not promoted as a standard tone chamber system until the announcement of the top-tension models. These had 20 holes although some have been found undrilled.

Fig. 11

Fig 11. The top-tension banjos featured a specially cast and machined stretcher band (A), into which fit square-head, washer-head bolts (B) to allow adjusting of the skin heads of that time without removing the resonator. The square-head bolts threaded directly into the cast zamac (pot metal) flange, and the armrest could be removed (to get to the bolts beneath it) by loosening a thumbscrew. The flattop tone chamber was officially announced with the introduction of this model. From an acoustical standpoint, the added mass of the cast stretcher band and heavy bracket bolts provided improved sustain. This, combined with the top tension model’s solid resonator gave this instrument unusual performance characteristics not found in Gibson’s lighter-weight models.

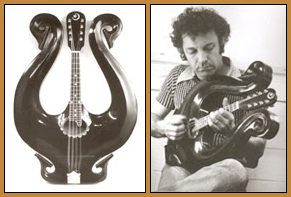

After several iterations of early label designs, The Company settled on this label, often referred to as the “lyre label,” and used it in most of its acoustic stringed instruments up through 1930, except for banjos, and Loar-signed instruments (F5 mandolins, H5 mandolas, L5 guitars, etc.). At first glance, the instrument on the label appears to be a lyre (an early U-shaped instrument, similar to the shape of the instrument in the label, with three to six strings and no fretboard).

What was not clearly visible is that Orville’s photo is blocking the fretboard of this instrument and that it is, in fact, a mandolin, not a lyre. I called Julius Bellson, former employee and historian at Gibson, and the discovery sparked his attention, for Julius had always thought the instrument in the label was a lyre. We were both intrigued by what Orville was trying to do in this design and I told him I “had to build one!”

To resolve my intrigue, I photographed one of these labels and enlarged the image until I arrived at a 13-15/16″ string scale, nut to bridge. Then, I sent one of the photos to Julius and I used the other as a template to build an instrument that resembled the one in the label.

Shortly after writing an article about this discovery for Pickin’ Magazine (June 1976), entitled “The Truth About a Lyre,” One of Orville’s original lyre mandolins came back to its home in Kalamazoo. The owner brought it to the Gibson plant for refinishing and to learn about the instrument’s importance and value, if any. Ken Killman, Gibson’s customer service manager at the time, called me and I scurried off to Kalamazoo to touch and photograph the real instrument and see how close I had come to building a replica without ever seeing the original.

The lyre is one of the earliest known stringed instruments and was often used as a decorative element on early objects. This clock, dating back to 1910, depicts a lyre whose design is very similar to the lyre in Gibson’s label.

To construct the lyre mandolin, I cut the rim from a solid piece, rather than bending it (as specified in Orville’s early patent claims). The rim is 1-1/2″ high, as on most of Orville’s early instruments, the soundboard is Sitka spruce, and the backboard is African mahogany. The severely-arched soundboard offered no flexibility which resulted in the amplitude and tonal qualities being rather poor. The photo of me playing it, was taken in 1976.

For the label, Orville’s photo was superimposed over the mandolin’s fretboard making it look more like a lyre than a mandolin.

Shortly after writing an article about this discovery for Pickin’ Magazine (June 1976), entitled “The Truth About a Lyre,” One of Orville’s original lyre mandolins came back to its home in Kalamazoo. The owner brought it to the Gibson plant for refinishing and to learn about the instrument’s importance and value, if any. Ken Killman, Gibson’s customer service manager at the time, called me and I scurried off to Kalamazoo to touch and photograph the real instrument and see how close I had come to building a replica without ever seeing the original.

The above instrument is now in the permanent collection of the University of South Dakota Music Museum in Vermillion, SD. In October, 2007, I was invited to the museum to give a presentation on The Lore of Loar, and had a minute to stop and see Orville’s lyre mandolin. Photo courtesy George Gruhn.

This version of Orville’s lyre-shaped mandolin (above) was an impressive sight and it was in rather good condition. Orville’s mandolin was built on a 3″ thick rim and there was a support bracket across the back of the peghead connecting to both of the two horns. (That bracket is actually visible on the label and can be seen as a curved line above Orville’s photo, between the peghead and each of the horns. I had no way of knowing from the label, that it was part of the instrument so I didn’t include one on my prototype.) As on Orville’s other early instsruments, the neck was hollow for about half of its length (I assumed that Orville did this for the lyre mandolin, since he did it on his guitars and mandolins, but I didn’t bother hollowing the neck on my clone). Somewhere along the way, it appeared that the original lyre-mandolin was refininished to natural wood, but we weren’t positive. The thought then came to mind that maybe there were two of these instruments.

Photo by Rosemary Wagner

As we investigated further, and compared this instrument to blow-up photo I sent to Julius, we realized that this instrument was different from the one in the label. It had a pickguard, the one in the label didn’t. The inlays around the soundhole were different on both instruments. The soundhole on this instrument was more oval shaped than the one on the label. And, the most telling clue was that this mandolin had the lyre label. So, it was resolved that Orville built at least two lyre mandolins. But clearly, there were never popular, and aside from being inside almost every acoustic stringed instrument the company made, it never made it to the catalog as a Gibson instrument model.

The original photo of Orville for the label can be seen at the very beginning of my introductory page on Orville Gibson (that lead you to this page). A round photo of it was graphically superimposed over a photo of the lyre mandolin to achieve the artwork in the label as shown above.

In June of 2006, the plot thickened. George Gruhn, Gruhn Guitars, Nashville, TN., called to share that he had just come in possession of yet another lyre mandolin. This one featured a larger peghead with star and crescent inlay and no supporting bracket on the back of the neck. The inlay around the soundhole was the herringbone purfling used on the early A and F model oval-hole mandolins, and the fretboard inlay features two dots at the 5th fret. So clearly, there were at least three lyre mandolins produced by Orville or his immediate workers.