Lloyd Loar

The man inside the name

The man inside the name

Instrument Design

Loar’s Patents

Classes at Northwestern

Lab Notebook, The Physics of Music

Loar’s Music

Research for Webster’s Dictionary

Loar’s Workbench

Virzi “Tone Producer”

Albert Shutt’s Patent

Bertha Snyder Loar Westerberg

Loar’s Instruments

Patrick Tobin, Loar’s Viola’s Voice

Preface

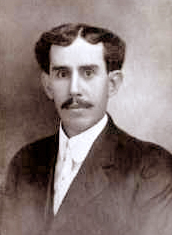

Over the more than four decades that I have been researching, presenting, and writing about Lloyd Loar, the focus has always been on his work and on his contribution to the world of music. I studied the what, when, where, and why, and focused much less on the who. The first four attributes could be gleaned from hard data; the who is another matter all together. In my work, I made some assumptions about Loar’s character and personal attributes but never felt that I had enough information to sum up the true character traits of the man. Over the years, the background information I had gathered kept taking shape, and I recently began re-reading many of his documents, this time to learn about the person behind the words as opposed to learning about the documents’ contents. I also reviewed notes I had from others who knew him or knew of him with some certainty.

While I never had the privilege of personally meeting Lloyd Loar (he died when I was three), I did have the honor of engaging with two people who knew him well; his second wife Bertha with whom I was very close during the last two decades of her life, and Ted McCarty, a past president of Gibson. I was also fortunate to have Louis Good share a letter with me that was part of his research on Lloyd Loar regarding an interview he had with Traugott Rohner, a student of Loar’s at Northwestern University in 1931 and 1932. I also had the opportunity to communicate with Mary Moss, a librarian and archivist who worked at Northwestern University when Loar was teaching there. And, I met a few other folks along the way who had a somewhat more distant relationship with Loar and fewer clear memories.

Bertha Loar

The complete story of Bertha Snyder Loar, Lloyd’s widow, is told elsewhere in this web site. Bertha was a dear friend, and I communicated with her almost daily for the last 22 years of her life. Bertha was Lloyd Loar’s second wife. Bertha married Lloyd in 1938 and had little direct knowledge about his work at Gibson. And, aside from accompanying him to various music trades shows, she remembered little about the specifics of his work. Her memories about him, his persistent goals, and his obsession with music, however, were clear. She loved him dearly and they were very close, but the center of Loar’s life was his music. Bertha commented that Lloyd was soft and pensive, somewhat shy, and very courteous and considerate of others. But she also saw the contrasting side, in which he was very persistent, very focused, and worked hard to get what he wanted. She was infatuated by his wit, creativity, and his quiet but persistent manner, and she often commented to me that some of my traits and my focus on music reminded her of Lloyd. These comments helped me to get a better sense and understanding of who Lloyd was as a person.

Ted McCarty

Ted McCarty joined Gibson in 1948, became president in 1949, and was with the company until 1966 when he resigned from Gibson and bought Bigsby, an electronics and effects-pedal company in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He grew Bigsby during the following 30 years and sold it to Gretsch in 1999. While consulting at Gibson, I’d frequently drop by to chat with Ted. Loar left Gibson 23 years before Ted worked there, so Ted had no first-hand knowledge of what Loar did for Gibson. But before joining Gibson, Ted worked at the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company from 1936 to 1948, and it was during this time that Ted had some interaction with Loar. Loar and Lewis Williams were attempting to get Acousti-Lectic company on its feet in the years following the Great Depression. During the 1930s, Loar had filed for, and was awarded more than a dozen U.S. Patents for keyboard actions and keyboard pickup systems. According to Ted, Loar was very persistent, persuasive, and aggressive in trying to license some of his ideas to Wurlitzer.

Julius Bellson

I also had the pleasure of spending a good deal of time with Julius Bellson and heard many tales about Julius, his brother Albert, and the Gibson Company of yesteryear. Julius talked about Loar as if he knew him, but the two never met, and the stories he shared were second hand. Julius joined Gibson in 1935 – ten years after Loar left – and was to become Gibson’s self-appointed historian in the 1960s and 1970s. Although Julius officially retired from Gibson around 1970, he’d go to the plant several times a week (he lived on Crown Street, just a few miles from the plant) and would often be called in to talk to journalists and others who came to the plant to learn about Gibson and its history. Julius’ primary memory of Loar was that he wanted to produce electric instruments and was very frustrated that management at Gibson did not support his ideas. (Although it was Gibson executive Lewis Williams who left Gibson to make electric instruments with Loar.)

Mary Moss began working in the library at Northwestern University in the early 1940s, and later became assistant archivist. She retired in the early 1970s after 30 years at Northwestern, and I had both the good fortune and privilege of communicating with her about Lloyd while she was still there. Mary remembered Loar for two main reasons: he was a frequent visitor to the library and was always engrossed in research, and, more vividly, he married a Northwestern student (Bertha) whose 18 year age difference – and the fact that she was a student – created a bit of a stir at the University. I don’t have notes on Mary’s exact description of Lloyd, but I do recall that Mary remembered Loar as being pensive and focused. Mary was very instrumental in helping me find Bertha, and for that I am forever grateful.

To further expand my understanding of Loar’s character, I have read more than a hundred documents written by and to him, and one thing that recently re-kindled my interest in writing about Loar, the man, was a June 15, 1929 letter he wrote to Karl Gerhkens, the head of Oberlin’s music department, the author of The Fundamentals of Music (1924), and someone Loar looked up to. In this multi-page letter, Loar writes about his interest in creating a research lab at Oberlin, and in reading this document, it is very easy to appreciate Ted’s and Bertha’s comments about Loar being very persuasive and persistent.

It has been more than 30 years since I spoke to Mary and Ted about Loar, and more than 12 years since Bertha and I spoke, so I am unable to remember and share their exact comments. What I do have, though, is a strong sense of the pieces of the puzzle of who Lloyd Loar was. As you read on, I ask that you accept my views as a reasonably accurate assessment of Loar’s character as developed through conversations and documents.

As a young man, Lloyd Loar was a highly-accomplished and highly-motivated musician who diligently pursued his music career. He was shy and somewhat reserved, yet very proactive and assertive in areas of importance to him. He had the conviction of someone who clearly knew what he wanted and pushed hard until he got it. Ted McCarty remembered him as being persistent, but polite, and someone who always had excellent arguments for the points he wanted to drive home. Ted commented that he respected Loar but really didn’t enjoy working with him because of his continual and constant reasoning.

Loar was what some would think to be a quiet “Type A” individual and always had more than two or three projects going at once. When one considers what he did in his short 57 years, it would appear that his accomplishments and involvements were enough for three people. He was an author, composer, music arranger, acoustical engineer, inventor, contractor/consultant, designer, performing musician, publisher, columnist, music teacher, and college professor. He composed hundreds of pieces of music, arranged dozens of music scores, authored 13 books, and was awarded 14 U.S. Patents.

Speaking of his compositions, I had the great fortune of hearing many of Loar’s pieces played by Bertha, an accomplished pianist. John Monteleone also had the pleasure of hearing Bertha play some of Loar’s music when I brought him to meet her. Sadly, Loar’s filing cabinet full of music was disposed of by an irresponsible conservator in Bertha’s final years and are now gone forever.

In a letter from Louis Good to Scott Hambly (archivist at The John Edwards Memorial Foundation, Inc.) dated February 18, 1971, Good shared information about Loar that he gleaned from an interview with Traugott Rohner, a student of Loar’s in 1931 and 1932. Rohner shared with Good that he had “high regards for Mr. Loar as a person and his advanced thinking as an individual, in the area of physics and acoustics of sound.” Rohner said that “Mr. Loar was a very kind and a very quiet man and dedicated to the physics of music. He was an original thinker and attempted to prove his theories by experimentation and to support them with academic reasoning.” He went on to say that “Mr. Loar was an introvert by nature and had very little social contact with the teaching staff of Northwestern. He was, for the most part, a loner and purposely kept to himself and his deep interest in the physics of music and the study of acoustics.”

Loar felt that the pinnacle of musical instrument design was the violin. In his Physics of Music class at Northwestern University, Loar spoke highly of the developments brought forth by Stradivari and taught that “the tone of the violin is one of the most efficient acoustically.” In that class he spoke of the individual features of the violin, and it is obvious by studying the features of the F5 mandolin that Loar attempted to emulate the innovations of Stradivari and bring those features into the 20th Century through his work at both Gibson and Acousti-Lectric. As a result, most of the key features that Loar specified for the F5, H5, and L5 Master Model instruments stem from the violin.

Supporting his feelings about the virtues of the violin, Gibson’s 1923 catalog features a persuasive section on “Scientific Principles” authored by Loar. Page 22 has a chart that compares the qualities of Gibson’s mandolins to “the perfect standard” – the violin. This article reveals the nature of a very focused, very persuasive, and exceedingly bright individual.

In a letter to Karl Gehrkens (June 15, 1929), on the very threshold of the Great Depression, Loar described his appreciation for pure research and a distaste for the business environment. Talking about the developmental work he was trying to achieve at Gulbransen with new piano systems, Loar wrote “A purely commercial institution is not an ideal place for this sort of research, there is too much necessity for turning knowledge into immediate cash; and if the said knowledge doesn’t turn thus quickly, no matter how important it is, forget it, and acquire some that is negotiable.” Innovation in music was a key focus for Loar, and in that same letter, regarding the struggle of working for profit-motivated companies, Loar went on to say “But I don’t care a lot of it, and would prefer that the rest of my years be free from it.” In the letter, he outlined his objectives for teaching at Oberlin and requested of Gehrkens that he be able to develop a music research department there, and he provided rationale for establishing such a lab. Unfortunately, his idea never came to fruition. Instead, Loar only taught as a professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Although Loar was a professor from 1930 until the time of his death in 1943, he was never freed of the business environment he so disliked, and he was plagued with the problems of supporting the ViviTone keyboard systems he developed with Lewis Williams. During these final years, while teaching, he had to travel extensively to fix mechanical and electrical systems that were failing.

Rohner also stated in his interview with Good that “Mr. Loar was a frail man and looked like a man that was not well nourished. He was not a very strong man physically. His body frame was small.” Contrary to Mr. Rohner’s opinion that Loar was “frail,” he had been a member of the quarter-mile track team while at Oberlin, was high-spirited, and very competitive. According to Bertha, though, Loar always liked a good cigar and may have smoked more than he should have. One clearly envisions a man who drove himself hard, took himself very seriously, was always on the cutting edge, all of which may have played a role in ending his life at a very young 57 years of age. On the morning of September 13, 1943, at 4:00, Lloyd Loar passed away in his home on Fargo Street in Chicago. The cause of death on his death certificate is listed as hypertension.

While Loar came from a Presbyterian family, he and Bertha followed the beliefs of Theosophy, the idea that all religions are part of a master plan or spiritual hierarchy that helps humanity develop to greater perfection. As such, Theosophy suggests that each religion is part of the greater truth. Bertha mentioned several times that Loar went on to do better work. I have no way of knowing if he was successful in attaining his ultimate spiritual goal, but clearly his work attests to the excellence of his Earthly endeavors.

Lloyd Allayre Loar made many contributions to the world of music through his developments of piano key actions and amplified instruments, but it is his advancements in acoustic stringed instrument technology while working for Gibson for which Loar is widely known today. “Lloyd was always searching for something,” his wife Bertha would remark, referring to his interest in musical developments. And, the instruments he played were always different in some way. The first Gibson F2 three-point mandolin he owned, shown in this cameo (below, left) from the Gibson 1908 “F” catalog, boasted a unique pickguard that covered and protected the end of the fretboard. The enlarged photo (center) shows how this pickguard extended across to the mandolin’s bass bout and went just to the edge of the soundhole. In the photo, the pickguard appears to be molded around the end of the fretboard as opposed to being elevated. (This cameo image was taken from the original photo shown on the previous “Loar’s Background” web page. The photo on the right, also taken from Gibson’s 1908 “F” catalog, shows the standard configuration of the early F2 three-point mandolin with it’s optional clamp-on fingerrest.)

Loar went to work at Gibson in 1918, the same year Orville Gibson left the company. But little is known of whether these two events had any relationship to each other or how close their relationship was. Under Loar’s guidance, soundboards and backboards for Gibson’s Master Model mandolins, mandolas, and guitars were carefully graduated from their thickest to their thinnest regions. For mandolins, this called for soundboards and backboards to be carved to about .110″ in the thinnest or “minimum area” (about 1″ in from the perimeter) and about .180″ at the center. Since these components were later “tuned,” the final thickness would differ from instrument to instrument depending on the stiffness of the wood, grain distribution, density, etc. Soundboards were also arched to give them strength. The graduation from the center outwards provided for a means of efficient distribution and transfer of energy (from the bridge outwards). This carving technique, often called “Stradivarius arching,” allowed the soundboard and backboard to “pump” like the paper cone of a common speaker, generating greater compression and rarefaction within the instrument’s air chamber; a movement that provided theses instruments with greater amplitude then their former counterparts.

Longitudinal tone bars were also “tuned” by thinning them to adjust the stiffness of the soundboard. The bass bar and treble bar were positioned in a non-symmetrical manner, and sized differently so that the treble side and bass side of the soundboard could be separately adjusted (i.e. the two tone bars were not symmetrically positioned). By removing wood from the tone bar, the soundboard would become less stiff, resulting in a lowered pitch. By tuning the tone bars to a specific note, Gibson engineers could be assured of likewise adjusting the soundboard to a known and very repeatable stiffness. The tuning process is so controllable that a whole-tone difference could be attained between the two tone bars. As a final tuning step, the f-hole openings were also “tuned”. To do this, the size of the f-holes was adjusted after the instrument was assembled, to achieve the final tuning of the instrument. As the f-holes were made wider (larger), the pitch of the air chamber would be raised until the proper note was achieved.

The “Stradivarius arching” or tortoise shell shape provided the backboard and soundboard with great strength without the need for additional structural bracing. But more importantly, the graduation from a thick center to a thin outer portion imparted to these “plates” the ability to evenly distribute energy from the center (where the bridge was mounted) outwards.

(This photo demonstrates the type of arching and shape of a maple backboard that was used on the F5 mandolins. The wavy lines across the backboard are caused by the curly maple figure.)

Cosmetic variations appeared in hand-rubbed “Cremona” finishes ranging from almost black to rich dark brown. Variations of white/black/white binding were used on the Loar-signed F5s and the instrument was adorned with either silver- and gold-plated hardware and either “fern” or “flowerpot” inlay patterns on the peghead. All featured dot inlays, as shown here. About 250 of these instruments were built by Gibson and Lloyd Loar personally approved the tuning, and signed the labels in each one (see labels, below). Loar followed the teachings of Hermann L. F. Helmholz (1821-1894) who studied the resonant frequencies of variously sized air chambers. Loar carefully sized the air chambers and f-holes of the instruments he designed to provide a correctly tuned space for each type and size of instrument. Since an adjustment to one part of the instrument effects the tuning of another part, one can appreciate the hours of trial and error that preceded the development and subsequent finalization of the dimensions of Gibson’s “Master Model” instruments. As final proof of the hand-tuning process, Loar gave his signature on a label inside the instrument attesting that “The top, back, tone-bars, and air-chamber of this instrument were tested, tuned and the assemble(d) instrument tried and approved ___(date)___.”

Each of the Gibson “Master Model” instruments featured a signed label which attested to the tuning process applied to that instrument. While Loar didn’t actually build the instruments themselves, he did test each one to ensure they were properly tuned, and then signed and dated the labels

Loar’s tunings would have been unusual for us today, because they were based on having concert pitch at C256, a tuning that has fourth octave A falling between A430 and A431. Today’s concert pitch is predicated on A440 which positions C at 261.63Hz. This misalignment of tunings is one of the main attributes that gives F5s their great voice, today. (For more information, you may wish to click here to download a study entitled What was Loar Hearing? – 1M.) During Loar’s tenure at Gibson he developed an A-model mandolin that boasted all of the features of the F5 but had a simple tapered peghead with a fleur-de-lis inlay, and a pear-shaped body that was absent of the body scroll and body points. This “A5” model featured f-holes but since the body was slightly smaller than an F5, the resonant frequency of the air chamber was naturally higher than an F5 requiring the f-holes to be smaller in order to tune the air chamber to a D#. The instrument had the famed “signature labels” (above) and while Gibson was later to make pear-shaped mandolins with f-holes, this model was never cataloged by Gibson. This instrument is richly detailed in our A5 Pro-Series Drawing set.

Another Loar contribution to the tonal characteristics of Gibson’s mandolins was addition of “Virzi Tone Producers” affixed to the inside of the soundboard on some of the “Master Model” instruments and on his personal F5 mandolin. The Tone Producer was a disc made of spruce with two f-hole-like apertures, which was affixed to the underside of the soundboard with a single rear foot and a double front foot. It was the intention of the Virzi brothers, who patented this design, that the Tone Producer would impart a better overtone series to the instrument. While the Tone Producer’s popularity did not survive to today’s instruments, it gained popularity with classical players during the 20s and 30s and was heavily promoted to performers on violin-family instruments. Loar was a consultant to Virzi and his photo and bio appear in the Virzi literature. His own personal viola (made by August Diehl) also boasts a Virzi Tone Producer.

While Loar did extensive work on electric keyboards and amplified stringed instruments, his association with those developments did not endure to today. By contrast, the name “Loar” is heralded as the penultimate creator of the bluegrass mandolin. Clearly, Bill Monroe brought the mandolin into the spotlight, but the sound we associate with Monroe’s instrument came from Lloyd Loar.

The F5 mandolin was a major departure for Gibson. It provided the same 13-15/16″ string scale as on previous mandolin models, but the F5 featured an extended neck with 12 frets clear of the body. The soundboard and backboard were carefully graduated and tuned, as were the tone bars and f-holes.

The A5 boasted many features of it’s F5 counterpart. One major departure from the F5 design was the positioning of the bridge high above the centerline of the body in what appears to be an attempt to gain more live soundboard area than was achieved on F5 models. This also called for an accentuated headblock. The f-holes are slightly further outboard than those on the F5 and are sized about 15% smaller than those on the F5 to deliver a lower-than-natural voicing of the instrument’s air chamber. The binding on the lower corners of the peghead are bent rather than mortised and the peghead’s binding joins in a mortised “V” joint at the top center of the peghead. Loar elaborated on the pear-shaped f-hole body with an even greater Venetian flair for his ViviTone mandolin designs (below). [The instrument pictured here was signed and dated on Sept 10, 1923.]

While not as popular as the L5 guitars and F5 mandolins of the period, the H5 Master Model mandola was another interesting development produced under Loar’s direction.This instrument is 11″ wide and almost 30″ long and features a carved soundboard and backboard with tuned air chamber as did other models in Gibson’s Master Model line. The H5’s fretboard connected to the body at the 13th fret (instead of at the 15th as on the F5) and it featured a 15-5/8″ string scale.

Some discussion in various luthiery chat rooms suggests that to achieve the correct body shape for the H5, “the commercially available F5 plans can be scaled up 15%.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading as the H5 has very different body proportions, scroll shape, bridge placement, peghead shape, f-hole position and scaling, fretboard shape, and more.

(Photo courtesy George Gruhn)

If one had to sum up and highlight Loar’s most significant contribution to acoustic instruments, it would have to be in the area of “tuning.” The art of tuning was not merely adjusting the strings to the correct pitch but rather tuning the various structural components of the instrument to specific pitches so that the whole instrument worked as a coupled system (acoustically speaking), producing the best tones possible from each of its parts and from the instrument as a whole. In this regard soundboards, backboards, tone bars, f-holes, and air chamber sizes were adjusted so that each element was tuned to a specific note that resided on a scale that used A440 as its calibration point (historically, A was not always 440Hz). With the entire instrument assembled, and strings tuned (also to a scale that also used A440 as their calibration point), the parts of the instrument responded harmonically to the strings’ energy rather than discordantly, and avoided any unwanted “beats” or overtones thus bringing forth the best dynamics and tonal qualities of the instrument. After his stint with Gibson, and excited by the potential of his developments for tuning mandolins and guitars, Loar carried his ideas to the massive soundboards of pianos (see US Pat 1,798,212 in Loar patents) which ignited further expansion of a new line of keyboard and fretted instruments under the name “ViViTone.”

Loar spent his later years (1935-1943) creating devices for amplifying musical instruments, developing keyboard actions, and creating tone producing systems for electric pianos. His approach to acoustic stringed instrument design was centered on two major aspects of construction: First, he strove to obtain maximum tone and power from the instrument by adjusting its components to most effectively drive compression and rarefaction (the two pressure-producing modes of sound waves). Secondly, appreciating that the instrument itself produced a note (or notes) which was part of the overall tone, he attempted to tune the instrument and its parts.

Loar was a performing artist, an engineering “artist,” and as we have discovered, an artist with pencil and paper. Uncovered with his personal papers were many drawings and sketches of instrument designs and instrument parts. One of many of Loar’s drawings, is this of the ViviTone clavier. It was drawn in pencil on a paper bag. c:1937

The speaker cabinet that accompanied Loar’s ViviTone Clavier features a 110v motor that rotates a fan-like blade. The blade turns in front of the powered-coil speaker as well as covering and uncovering an opening to the cabinet itself. This feature provided a tremolo that added timbre (tone “color”) to the erstwhile poor sound of his early electronic amplification system.

As testament to Loar’s work, his personal clavier (shown here) was in perfect tune when it was first discovered and unpacked 50 years after his death. Unfortunately, the War years, coupled with lack of financing, made it difficult for Loar to advance his art and his business, and the production of ViViTone instruments came to premature end.

Paper-cone speakers were in their infantile stages during the period that Loar was playing with electronic amplification, and the tube-amps and electronics he used were prone to background noise and hum. To add vibrato and improve the tonal qualities of these early systems, Loar placed moving baffles in front of the speakers in his speaker cabinets. In the system shown above, a spinning blade blocks the output from the speaker as well as from the bass response and resonant frequency of the speaker’s cabinet. In another system, (not shown) a vertical paddle turns in front of a speaker to induce a tremolo effect. Loar used foot control buttons to turn the motors on and off. Unfortunately, the mechanics were not very efficient and the motor, fan belt, and spinning blades were a bit noisy.

Loar worked hard to develop his line of ViViTone instruments. He focused to provide instruments that would be powerful and would stay in tune (a frustration spurred by the poor steel strings of the day). His ViViTone Clavier was an amplified instrument that used small bars that would chime when tapped by the key action. Since the bars were not stretched (as strings are in a piano), it was his intention that these instruments would always be in tune. His dream came true; his clavier (above) was still in perfect tune when it was uncrated 50 years after he packed it!

Following the design of Loar’s prototype for his electric viola the production model for his ViviTone electric violins featured a flat soundboard with painted f-holes (no air chamber), a heavy ebony fretboard, and an electromagnetic pickup. (Photo courtesy of the National Music Museum, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, South Dakota.) For more information on the Loar collection at the museum, click here.

The ViViTone guitar and ViViTone mandolin were available in both acoustic and electric models. The ViViTone instruments featured f-holes, white pegheads with a black silk-screened logo and a dark, hand rubbed Cremona brown finish.

The non-keyboard ViViTone instruments were unique and featured a laminated and very-rigid rim with both the soundboard and the backboard made from spruce. Coil-wound pickups were employed to amplify sound, and the soundboard, tone bars, backboards, and f-holes were carefully tuned to deliver a rich, balanced tone. While these instruments delivered a new and exciting sound for musicians of the period, the lasting effects of the Depression and the beginning effects of World War II smothered the music Loar was making and prevented Loar from raising the needed cash to grow his business and market his line of instruments. ViViTone and Loar’s dream came to a screeching halt. Early in 1940, While partner Lewis Williams continued to make ViViTone guitars in Kalamazoo, Loar went back to Chicago to look for investors, promote the keyboard line, help Frank Holton sell his business, and do whatever he could to promote his designs and ideas. But through his frustrations, and probably to keep his mind fresh, Loar continued to teach music theory at Northwestern University — the one thing he loved most — until his death in September of 1943.

Loar received 14 U.S. Patents during his career. His most prolific design period (from a standpoint of developing patentable ideas) appears to have been from 1927 to 1937. Nine of the 14 patents relate to piano designs and keyboard actions, the others to stringed instruments. However, all of them speak to his focus on improved tone and amplification.

Loar best summed up his lifelong objectives in developing the ultimate musical instrument in this opening statement of his fourth patent:

“The main objects of my invention are first, to provide a musical instrument capable of tone production in which the note produced is approximately 90% fundamental and only 10% overtones and having a perfectly even scale with every tone developed to its maximum of quality.”

As these patents clearly demonstrate, the work of Lloyd Allayre Loar proved him to be a pivotal force in musical instrument advancements. Truly, he was an acoustical genius and musical instrument designer way ahead of his time.

While all of his patents clearly demonstrate his incredible thought process and ingenious mind, Patent 2,046,331 (July 7, 1936) talks about an amazing departure from the viol family’s soundpost. In this design, a simple linkage system drives the soundboard and backboard together and apart in unison to improve compression and rarefaction in the air chamber. A marvelous and yet simple idea!

The following is a brief excerpt of each of his patents (full copies are available from the US Patent and Trademark Office (www.uspto.gov): (My appreciation to Arian Sheets at the National Music Museum, Vermillion, SD, for discovering some patents that I had not found.)

US Pat 1,798,212; March 31, 1931

Loar’s first patent was a true indication of his focus on tuning the various components of musical instruments. In this Patent, he claims his ideas for the alignment of the sound-board’s grain, adding apertures (visible along upper edge of lower drawing) to the edge of the soundboard to make the soundboard more supple and to help tune the air chamber, positioning and tuning the soundboard’s braces, and general tuning of the piano’s air chamber. Loar points out in this patent that his improved soundboard design was efficient enough to permit the instrument to be strung with twins rather than triplets of strings per note.

Loar was living in Chicago at the time he applied for this patent.

This patent was applied for on Dec 24, 1928 and was assigned to the Gulbransen (piano) Company of Chicago, Illinois for whom Loar was working as a consultant.

US Pat 1,815,265; July 21, 1931

Following from his soundboard development in the previous patent, Loar set out to improve on the piano’s bridge system. As with his previous studies on mandolin and violin bridges, he strove to develop a bridge that could rock on its axis to take advantage of the strings’ longitudinal (rather than lateral) vibrations. His bridge design was intended to amplify the torquing motion of the bridge and to control how that bridge energized the soundboard to which it was connected. The cantilever positioning of the bridge (as seen in the middle drawing) enabled great mechanical advantage in transferring the strings’ energy to the soundboard.

Loar was still living in Chicago at the time of this patent and applied for it on July 10, 1929. As with his previous filing, he assigned this patent to the Gulbransen Company of Chicago, Illinois.

US Pat 1,821,978; Sep 8, 1931

The application for this patent was filed on July 10, 1929. The patent describes Loar’s design of a picking action for producing a harpsichord effect and produce “special effects” in the playing of a regular piano. As opposed to add-on accessory products of the period, this technology of this patent is designed to apply a “wiping effect” to standard piano actions and to enable the entire set of hammers to shift their position so they would attack only one string (of the double or triple sets of strings in the piano).

This patent was assigned to Gulbransen Company of Chicago, Illinois.

US Pat 1,992,317; Feb 26, 1935

This filing created a major breakthrough in instrument design. The patent describes a piano with tuned “reeds” or bars whose adjustable length determined the pitch to which they vibrated. When struck by small hammers, and amplified, the reeds would emit a piano-like tone. A further objective of the patent was to create an inexpensive keyboard instrument with easy access to the pickups. And, since the reeds were not stretched wire (like their piano counterparts) they would always be in tune.

Loar proved to be right. When his personal version of this piano was unpacked 50 years after he crated it, it was still in perfect pitch!

Loar was living in Kalamazoo, Michigan when he filed for this patent and assigned it to his new company, the Acousti-Lectric Company of Kalamazoo, makers of ViviTone electric pianos. This application was filed on Jan 27, 1934.

U

S Pat 1,995,316; March 26, 1935

This patent was filed on the same date as his previous patent (Jan 27, 1934) and was basically an extension of his previous work. In this patent, Loar focused on an improved magnetic pickup, a pedal controlled poten-tiometer, and an improved method to transfer the pianist’s energy “whereby the intensity of the tone is controlled directly by the force with which the keys are struck.” Again, he calls out the goal of producing an economical and lightweight piano. (The ViViTone Clavier which he manufactured weighs about 110 pounds compared to the 550 pounds of a traditional upright.)

In this patent, Loar also describes that each rod or “reed” would have it’s own electronic sensor to amplify the sound.

Loar assigned this patent to the Acousti-Lectric Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

US Pat 1,995,317; March 26, 1935

This patent was also filed on the same date as his previous two patents (Jan 27, 1934) and describes a unique key action with special picker jacks, picks, friction, and leverage points to improve the picking action without mechanical interference. While the text of this patent also speaks about a bar that touches all of the strings in their center to evoke the second partial (harmonic) and raise the pitch of the whole instrument by an octave, that feature is not called out in any of the patent’s claims.

This patent was assigned to the Acoustic-Lectric Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

US Pat 2,020,557, Nov 12, 1935

Loar’s next effort was to amplify guitars, mandolins, and violins by developing an instrument with two soundboards and electronic pickups. In this patent, Loar describes that both soundboards have tone bars and that the inner or “secondary” soundboard is driven by the outer or “primary” soundboard. Of great interest is that the primary soundboard has only one oval soundhole (upper drawing) and the secondary soundboard (inside the instrument) has two F-holes, very reminiscent of the Virzi Tone Producer. He describes placing the soundhole under the bridge (with the bridge resting on the edges of the soundhole) because “the vibration in the board weakens as it travels away from the bridge so that the edges of the soundhole vibrate with the greatest possible intensity … and adds to the efficiency.”

This patent, filed May 14, 1934, was also assigned to the Acoustic-Lectric Company.

US Pat 2,020,842; Nov 12, 1935

This patent was issued on the same day as his previous patent and describes an amplification means for an electric violin or viola. In this design, the instrument has no air chamber, but merely a simple spruce soundboard with no apertures. The pickup is mounted on the soundboard and the bridge is mounted directly on the pickup.

(The prototype of this instrument was in my possession for several years. The instrument I owned had the pickup mounted on the soundboard, and not under it.)

This patent also features a “pedal-operated circuit-controlling device” for altering the volume — in essence, the earliest known foot operated volume control. Loar also used this pedal control with his amplified F-5.

This patent was filed on July 31, 1933 and assigned to the Acousti-Lectric Company.

US Pat 2,025,875; Dec 31, 1935

After Loar’s extensive work on electronic amplification systems, this patent clearly expresses Loar’s realization of the attributes of non-amplified instruments. This patent describes a guitar which is switchable between amplified, non-amplified, or both by changing the internal components through a drawer in the side of the guitar. Unlike the bridge claimed in his previous guitar patent (2,020,557), the bridge in this guitar does not rest on the upper soundboard. Instead, it contacts an internal support which can be altered to either direct the string’s energy to the back or “belly” soundboard, or past a horseshoe-shaped magnet which surrounds an “armature” to generate electrical energy to be amplified.

(An interesting idea which made me chuckle in light of the work on my patent 4,433,603.)

Loar filed this patent on Jan 27, 1934 and assigned it to the Acousti-Lectric Company.

US Pat 2,046,331; July 7, 1936

This was the first of two patents granted to Loar on the same day, and this Patent clearly demonstrates Loar’s genius in the most incredible method to drive the soundboard AND backboard since the invention of the soundpost! Here, Loar explains his idea for a bridge which rests on a horizontal lever. The lever has one foot extending to the backboard and another foot extending to the soundboard. Through this linkage, the strings’ energy is driven to both the backboard and the soundboard at the same time. Unlike the soundpost in the viol family, as the backboard is driven downwards, the soundboard is driven upwards, and vice versa, which “doubles the amount of compression and rarefaction.” Loar’s patent describes how the feet can be glued in place to facilitate construction or can be movable to change the leverage points and thus the tonality of the instrument. The soundboard and backboard are both described with longitudinal tone bars and the backboard is set in from the stiff rim, as on his ViviTone guitars. Amazing!

US Pat 2,046,332; July 7, 1936

This patent was filed on the same date (Jan 27, 1934) as one of his earliest patents (U.S. Pat. No. 1,992,317) and, like the following patent (U.S. Pat. No 2,046,333), is a subset or “division” of that initial patent.

In this patent, Loar focused mainly on: developing a flexible mounting method for his “reeds” so they could vibrate at both ends, a method of mounting the reeds so they could produce a vibrato, a way to mount the reeds so there was no mechanical interference, an improved means of picking the reeds, and to provide a way to have ready access to the pickups through the back of the instrument.

There were 24 claims in all.

US Pat 2,046,333; July 7, 1936

This patent was a subset or “division” of a separate patent (below) filed on the same day of January 27, 1934. In this patent, Loar describes his design for a unique action for clavichords and harpsichords which provided for a “means for plucking the strings to initiate the vibration thereof without mechanical interference.” In addition, the patent called out a method to utilize a series of long coil-wound pickups which would be positioned near a keyboard instrument’s strings, basically transversing the entire harp of the instrument, to sense the strings’ movements and then amplify them.

Loar’s prototype of this keyboard action is shown in the sidebar, below. The prototype, now almost 70 years of age, is still fully functional.

Loar was still living in Kalamazoo at the time of this filing and assigned this patent to the Acousti-Lectic Company of Kalamazoo.

US Pat 2,085,760; July 6, 1937

This patent, Loar’s last, is very interesting. Rather than describing a new design, it is instead a reiteration of his earlier patent, US Pat 1,995,316. The drawings and opening statements are virtually identical with minor modifications. However, the 10 claims of this patent (1,995,316 had 22 claims) are carefully and concisely reworded to assure the ultimate protection of his design and ideas for a tuned “reed” clavichord.

The design still speaks about tuned “reeds” which float free in the air and are secured at one end, the specific striking mechanism and keyboard action, a means to control the intensity of sound, the portability of the amplifier, and the transfer of energy from the keys to the “reeds.”

The application was filed on March 16, 1935.

A typewritten attachment states that this patent, formerly assigned to Acousti-Lectric, was later assigned to the Vivi-Tone Company.

US Pat 2,185,734; Jan 2, 1940

This was Loar’s last patent. It describes a very unique plucking (“plectrum”) action by which the strings of this electronic harpsichord were excited. The patent describes a pendulum system to efficiently pivot the plectrum away from the string after it is plucked.

The application was filed on October 7, 1937.

This patent was assigned to Frank Holton & Co., Elkhorn Wisconsin.

Patent No. 2,046,333

This is Loar’s prototype of the picking action described in his patent No. 2,046,333. The device has a delicate plucking mechanism that picks a string stretched vertically in the frame to the left. The white line at the bottom right of the photo is the inside edge of the ivory piano key. The prototype is of one key only, and is still very functional today.

During the years following Loar’s short tenure at Gibson, he was very focused on teaching during the summer months in The School of Music at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Here is an outline of his classes and responsibilities from 1930 until his death in 1943. (The following listings are taken directly from the The School of Music’s class schedules.) It should be remembered that his professorial efforts were during the period of The Great Depression and I am sure Loar welcomed the income and employment opportunity. (Please see my “Notes” at the end of the listing.)

1930 – June 23 to August 1

I8b. The Physics of Music – The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Credit – 3 hours. Mr. Loar. (This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours.) 1:30-3:00, Room 37, Fisk Hall.

1931 – June 22 to July 31

I8b. The Physics of Music – The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Credit – 3 hours. Mr. Loar. (This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours.) 1:30-3:00.

1932 – June 18 to July 29

D5. Advanced Theory. A review for graduate students and others who have completed thrre years of study in the field of musical theory. Harmony, counterpoint, form, orchestration and original composition. 2 hours. Mr. Loar. 12:00, Music Hall 2.

I8b. The Physics of Music – The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. 3 hours. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 1:30-3:00, Fisk Hall 37.

1933 – June 17 to July 28

D5. Advanced Theory. (2) A review for graduate students and others sho have completed thrre years of study in the field of musical theory. Harmony, counterpoint, form, orchestration and original composition.

H5. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. Mr Loar.

1934 – June 23 to August 3

I8b. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. 3 hours. 1:30-3:00. Mr. Loar. Fisk Hall 37. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours.

1935 – June 22 to August 2

H5. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Music Ad. 53

I8b. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. 3 hours. 1:30-3:00. Mr. Loar. Fisk Hall 37. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours.

1936 – June 22 to July 31

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk Hall 37.

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Music Ad. 53

1937 – June 21 to July 30

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Music Ad. 53

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk 37.

1938 – June 20 to July 29

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Music Ad. 53

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk 37.

1939 – June 17 to July 28

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Music Ad. 53

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk Hall 317.

1940 – June 22 to August 2

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00-1:00. Mr Loar. Student Union 107

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk Hall 317.

1941 – June 23 to August 1

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00. Mr Loar. Music 107

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of various wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. Mr. Loar. This course will be accepted toward a degree as either a music elective or in lieu of Liberal Arts requirement to the limit of three semester hours. 2:00-3:30, Fisk Hall 315.

1942 – June 22 to July 31

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00. Mr Loar. Music 8

C25. The Physics of Music – (3) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of wind and stringed instruments, piano, organ, and voice; radio. 2:00-3:30, Mr Loar. Fisk Hall 315.

1943 – June 21 to July 30

C9. Vocal Composition. (2) The art song. Study of the correlation of the rhetorical principles of poetry and music. Class demonstration of types of art song, combined with individual experiments. 12:00. Mr Loar. Music 8

C25. The Physics of Music – (4) The scientific side of music. Composition of tone; tone color or timbre; sound waves; vibration; resonance; acoustics of wind and stringed instruments; the piano and pipe organ; voice acoustics; radio. 2:00-3:30, Mr Loar. Fisk Hall 315.

1944 (cataloged, but no dates indicated)

C25. The Physics of Music – F-W (4) Sound, noise, tone, pitch, intensity, timbre, vibration, resonance, sound waves. Acoustic analysis of all wind and stringed instruments, voice, amplified instruments, recording, radio, practice rooms, and studios. F 1:30-3:30, Mr Loar.

Notes:

1) It is interesting to note that from 1930 to 1942, The Physics of Music course was a 3-credit program. In 1943 it became a 4-credit program (although no additional hours or a lab were added).

2) From this list, we see that Loar taught three programs: The Physics of Music, Vocal Composition, and Advanced Theory.

3) Loar became ill at the end of July, 1943 and did not complete the last lecture of The Physics of Music class.

4) It appears that The Physics of Music course, as listed in the 1944 class catalog, was to have richer content on acoustics than previously, and included study of “amplified instruments” and “recording.” Had Loar lived to give this class, it would have been one of the first classes ever given on amplified instruments, but unfortunately, Lloyd Loar passed away in September, 1943.

5) A reproduction of the class notebook from the 1943 The Physics of Music course is available from us. Click here for more information on The Physics of Music notebook.

6) The spelling of “acoustics” is not a typographical error. It was spelled this way through around 1931 when one “c” was dropped and the word became “acoustics.’

Among the many pieces of memorabilia that Loar’s widow Bertha entrusted to my care was a well-illustrated lab note book entitled The Physics of Music prepared by one of Professor Loar’s students from a class at Northwestern University during the summer of 1943. This was to be Loar’s last class. As dated in the book, the first lecture was given on June 23, 1943 and class continued for 11 lectures until Loar became ill in the summer of that year, just one month prior to his death. Sadly, lecture 12 was never given and one can only surmise what his wrap-up would have been.

I have transcribed the notebook verbatim and have scanned all of the illustrations in their original form with the hope of preserving as much as possible of what Professor Loar might have drawn on the board. The text has been appended with margin notes where I felt clarification and expansion of some of the ideas was necessary. And, in an added effort to maintain the original integrity of the text, Rosemary Wagner carefully edited the manuscript with the goal of preserving the student’s spellings, punctuation, and language of the day.

The text goes through some of the basics of musical acoustics, how sound is produced by various instruments, the job of air chambers and apertures, how strings produce sound, what the soundpost in a violin does, and more. References are made to tuned air chambers and apertures. Loar refers to the violin as the “king” of string musical instruments and tells why, and he expresses dissatisfaction for the inability of members of the lute family (which includes mandolins, guitars, etc.) to produce a quality tone.

It’s a wonderful piece of history filled with lots of good data from the guy who gave us the F5 mandolin!

Although none of Loar’s hand-written music survives him, many of his creations and arrangements went into print. Some of his work was published as individual sheet music and others were published in various books. When Lloyd became part of Gibson’s traveling music roadshow in 1913, at age 27, the company published and distributed some of his work as a marketing tool. Here is one example of Loar’s work, the second-mandolin portion of Shubert’s “Marche Militaire.”

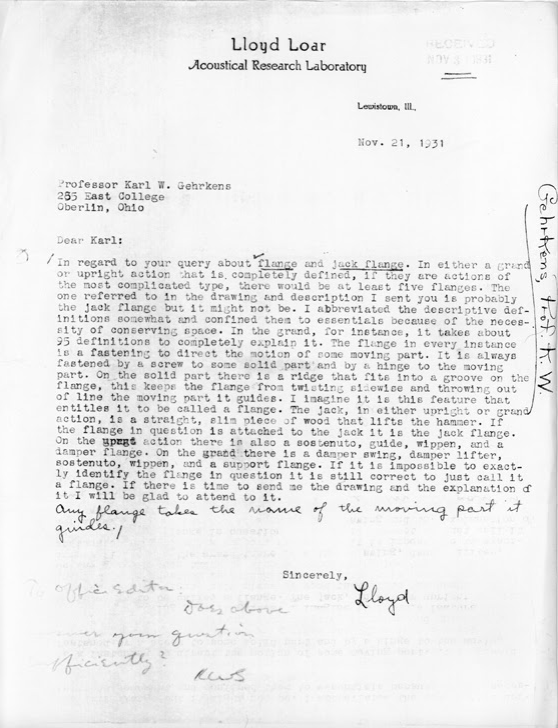

Professor Gehrkens’ correspondence, chiefly with Paul W. Carhart, the Managing Editor of Webster’s Dictionary, indicates that Loar helped with such questions as: how castanets are played, whether there should be a separate musically oriented definition of resonance, what a piano action looks like, and more.

Here is a letter from Loar to Gehrkens dated November 21, 1931.

In regard to your query about flange and jack flange. In either a grand or upright action that is completely defined, if they are actions of the most complicated type, there would be at least five flanges. The one referred to in the drawing and description I sent you is probably the jack flange but it might not be. I abbreviated the description definitions somewhat and confined them to essentials because of the necessity of conserving space. In the grand, for instance, it takes about 95 definitions to completely explain it. The flange in every instance is a fastening to direct the motion of some moving part. It is always fastened by a screw to some solid part and by a hinge to the moving part. On the solid part there is a ridge that fits into a groove on the flange, this keeps the flange from twisting sidewise and throwing out of line the moving part it guides. I imagine it is this feature that entitles it to be called a flange. The jack in either upright or grand action, is a straight, slim piece of wood that lifts the hammer. If the flange in question is attached to the jack it is the jack flange. On the upright action there is also a sostenuto, guide, wippen, and a damper flange. On the grand there is a damper swing, damper lifter, sostenuto, wippen, and a support flange. If it impossible to exactly identify the flange in question it is still correct to just call it a flange. If there is time to send me the drawing and the explanation of it I will be glad to attend to it. Any flange takes the name of the moving part if guides.

Sincerely,

Lloyd

No great historical revelations here, but fun to be able to peek up close at the stuff on Loar’s workbench as shown in this original photo. (Photo taken in Gibson’s original factory building, Kalamazoo, MI.)

A: The earliest version of the adjustable mandolin bridge designed by Gibson featured an aluminum saddle. These were in production for about a year. The mandolin that Loar appears to be picking with his right hand has a later period F5-style two-piece adjustable bridge with an ebony saddle.

B: A bridge base with an especially large base (apparently for a mandola) sitting on a box of other bridge bases and parts.

C: An early quick-winder (with handle facing away from us, and the socket for tuner’s knob on the left).

D: Several Virzi Tone Producer plates. Most of them have the bottom part of their feet broken off and it appears that these are test Tone Producers that have been removed from instruments.

E. Blocks of Virzi Tone Producer feet (upper one is the forward foot and lower one is the rear foot). The final thinner feet were cut from these blocks (as seen on the Tone Producers closest to the bottom of the photo.

Loar’s wife Bertha said that “Lloyd enjoyed a good cigar,” and from looking at his workbench, it is obvious that he put the cigar boxes to good use!

Even before the time of Antonius Stradivarius, Joseph Guarnarius, and Nicholas Amati, Italy began to earn its well deserved reputation as the breeding ground for luthierie giants. Further south, on the island of Sicily, in the village of Palermo, Giuseppe Virzi Sr. continued the heritage of the family-owned violin and pipe organ repair business. As is the European tradition for offspring to inherit and assume the craft of their parents, sons Joseph and John Virzi seized the opportunity, but took their family’s heritage to the New World in search of fame and fortune.

In the beginning of the 20th Century, Joseph and John moved to the United States, took up residence on upper East Side of Manhattan (124th Street), and sought to take advantage of the surge in popularity of acoustic string music. Boasting a line of fine violins, violas, and bass viols, the Virzis opened a sales office at 503 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

While the economic opportunities of the U.S. market offered great potential for violins from Italy — a natural connection for the two Virzi brothers — it is interesting to note that the Virzis instead turned to Heron-Allen and Alberto Bachman of Marchneukirche, Germany to produce their instrument line.

By the late 1920’s, their offerings featured six models; “Virzi Type,” “Type Virzi,” “Type Maestro,” “Type Master,” “Type Cremona,” and the “Semi-Strad” Type. The leading model had a retail price of $250 (a price comparable to Gibson’s F5 mandolin of that period). In addition to Virzi’s line of instruments, the company’s offerings included a full complement of strings, cases, bows, accessories, and the service of installing a unique “tone producer” in violins (at first) and then in a wide range of stringed acoustic instruments.

The Virzi Patent

Giuseppe Virzi was awarded U.S. Patent No.1,412,584 on April 11, 1922. The patent, which was applied for in 1920, was very simple in nature and describes only the fact that one or more soundboards could be supported inside such instruments as guitars and violins. It further describes that the plates could be attached to each other with dowels, and that the plates could be arch shaped.

It is not unusual for a patent to be somewhat dissimilar from a product that emanates from its claims, and this was the case with the Virzi Tone Producer. Rather than multiple plates, as described in the patent, the Virzi Tone Producers in common production were single plates. And rather than being arched, they were flat plates.

Of further interest is that the claims of the patent do not boast any of the contributions to tone generated by the plates, just that they are suspended inside the instrument.

The Tone Producer

A leading attribute of the Virzi violins was the addition of a secondary soundboard or “tone plate” (they also called it “Tone Amplifier,” and “Tone Producer”) which was affixed to the soundboard by either two or three feet (depending on type of instrument). The Tone Producer was a thin disk of particularly wide-grain spruce which was intended to be highly sensitive to the amplification of vibrations sent to its surface via the feet. The plate was rendered additionally delicate by the two f-hole-like slits which were to make the outer wings of the plate as free and limber as possible. The key to the functionality of the Tone Producer was in supporting the plate from it’s center as opposed to supporting it around its rim.

What’s behind their discovery

From an acoustic standpoint, plates (soundboards, backboards) secured along the rim vibrate in specific patterns and modes that are unlike plates secured in their center. Since the Tone Amplifier was held in the center, rather than by the rim, it was free to vibrate in different modes from the way the rim-secured soundboard and backboard could vibrate, and thus it emitted an entirely different series of overtones or “partials.” Additionally, the partials, especially the higher numbered partials, are more easily emitted from this thin, airy disk than from a more rigid soundboard.

Partials are subsets of vibrational modes and there is a specific order to their frequency, volume, and vibrational pattern. As it relates to a musical string, the lowest note at which a string vibrates is called the “fundamental.” This occurs when the string vibrates in one complete motion. When the string vibrates in halves (such as when we play a string and touch it lightly at the 12th fret; half it length) it is forced to vibrate in halves. This is referred to as the 2nd partial and the sound we hear is called a “harmonic.” On a given musical string, we can detect up to 18 or 20 partials until we either go above the human audible range (approximately 18,000 Hz or we are unable to define a partial.

We can force a string to vibrate in partials by touching it at certain point along its length, after it is played, which causes a null and forces the string to vibrate in segments. The sound we hear is called a “harmonic,”

Like strings, plates or soundboards have vibrational modes of their own. And, these modes are determined, in part, by whether the plate is secured along its rim or at it’s center. The Tone Producer provided this added and unique feature of enabling the amplification of different partial modes.

All Virzi violin models featured the “Tone Amplifier” which was affixed to the bass bar via two feet. In violins, viols, and bass viols, the Tone Amplifier was a singular, long elliptical disk.

While Virzi also referred to its Tone Producer as a “Tone Amplifier,” the disk, suspended inside the instrument, had no affect on the compression or rarefaction emitted from the instrument and thus it had no affect on its amplitude (loudness). In fact, since the disk was attached to the soundboard it took additional energy to drive it — an issue which was not a problem for the violinist’s powerful bow, but proved to be a complaint for the mandolinist’s pick. The reference to the word Amplifier suggested that the disk would enhance the quality of the overtone series and make them more audible.

In addition to installing the Tone Producer in their own violins, Virzi provided a service of installing Tone Producers in non-Virzi violins and their work attracted the attention of Lloyd Loar.

Loar’s personal viola was a full-size 1875 August Diehl which he had outfitted with a Virzi Tone Producer in 1922 (see label below). Virzi’s catalog featured a letter from Loar in which he attests to his viola’s improved tone:

Letter from Loar

Numerous world renowned musicians received the honor of a cameo in the 1929 Virzi catalog, but a full page was dedicated to Lloyd Loar’s comments on the attributes of the Virzi Tone Producer in his Diehl viola.

“I have thoroughly tested and inspected my viola in which you recently installed your Tone Producer. It pleases me greatly. In my opinion, you have contributed one of the most noteworthy improvements applicable to the construction of all string instruments of which there is any record in the last two hundred years.

This opinion is not alone based upon the sense of hearing, but is reinforced by scientific tests much more final in their testimony.

Testing the tone of my viola, I find that: previously those notes having the most pleasing tone color of any possible to the instrument under the most favorable conditions had but twelve [audible] partials or overtones. I am now able to identify fifteen and find indications of three more which are apparently too high in pitch to register definitely [to the human].

Parallel to the above and offering the evidence of hearing instead of science, my ear tells me: (1) The tone is richer and mellower. (2) It responds more easily and quickly to the bow, a suggestion of a ‘wolf’ tone at F on the G string is gone, and the tone is more powerful. (3) The pitch of the air chamber is not changed, neither is the characteristic tone color of the instrument.”

….. Lloyd Loar, M.M, Acoustic Engineer

The Virzi labels in Loar’s 1875 August Diehl viola are different from labels used in the Gibson Mandolins of the same period. Here two labels were applied; one says “J&J Virzi” and the other is a small Virzi company label with the date “anno 1922” hand written at the bottom. This Virzi Tone Producer is not numbered.Those in Gibson mandolins and guitars were numbered with a special Virzi label.

The Virzi Tone Producers for violins were oblong-shaped and had only two “feet” compared to the Tone Producers for mandolins (left) and guitars which were round and had three locating points which were both glued and pinned in place for structural integrity. This Tone Producer came from a 1923 Gibson F5 mandolin.

Some Tone Producers found their way to Gibson’s L5 guitars (as well as being installed in other non-Gibson guitars). When used in these instruments, the plates were tear-drop shaped and attached to the soundboard with feet similar to those in the photo.

Loar became enamored with the idea of using the Tone Producer in fretted stringed instruments and was instrumental in licensing Virzi Tone Producers for installation (during production) in many Gibson mandolins, mandolas, and guitars.

The Virzi Tone Producer intended for mandolins, mandolas, and guitars was a round disc with two slit openings somewhat resembling f-holes. Two bridges held the Tone Producer in place. The double-footed bridge was secured behind the mandolin’s f-hole centerline and the single foot attached nearer to the tailpiece.

All of the Tone Producers I have seen have had very wide grain (the wide grain wood being more supple than their narrow grain counterpart). It is interesting to note that most of the tone producers were not well crafted (note misshapen circle in f-hole in photo above.)

Although the Virzi Tone Producer clearly imparts warmth and tone, many of the Tone Producers in Loar-signed F-5 mandolins have been removed by musicians (or their repair persons) with the goal of achieving more power (commonly referred to as “bark”) in favor of tone (an act which Loar would have despised since the air chambers of these instruments were “tuned” with the Virzi Tone Producer in place).

Photo courtesy of Gregg Miner and Jack Shutt

Albert Shutt was a musician and instrument designer from Topeka, Kansas who introduced many innovative ideas for guitar, mandolin, and harp-guitar. Of special interest as it relates to the instruments developed by Lloyd Loar and The Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co. Limited in the early 1920s were the features Shutt employed in his mandolin design. These included an arched soundboard and backboard, f-holes, elevated fretboard, body scrolls, and a narrower fretboard whose width and taper were surprisingly identical to that of the F5 mandolin. However, Shutt’s soundboard design did not feature tonebars, and the body was somewhat smaller than that of the F5 mandolin. His soundboards and backboards were taped to add a bit of strength and inhibit grain cracking.

Shutt received a U.S. design Patent #40,564 on March 8, 1910. The patent had a seven year life, which meant that by 1917, anyone, including Gibson, was free to employ the design features in their instruments.

Shutt’s mandolins featured an elevated fingerboard extension. This design pre-dated the use of elevated extensions on Gibson mandolins and guitars.

The Shutt mandolins where finished in a honey-brown color and featured an ebony fingerrest.

The machines were set into the peghead and the back of the peghead was covered with a plate (the plate pictured here is not original).

The soundboard was reinforced with tape to prevent checking and cracking, and the instrument was absent of tone bars or braces.

For more information about Albert Shutt and his instrument designs, please visit http://www.harpguitars.net/history/shutt/shutt.htm

Bertha Snyder Loar Westerberg, c:1923

My research into Lloyd Loar spans three decades. During that time, and especially over the first ten years, I was relentless in attempting to uncover every speck of dust that lead to Loar. I traced school records, music resources, early magazines, military records, American Expeditionary Force service during WWI, passport records. college records, and everything else I could get my hands on. I am deeply appreciative to the many service agents in each organization who helped me with my research and linked me to the next step.

One key discovery was in learning about Lloyd’s second wife, Bertha Snyder.

Bertha and Lloyd at Roger’s Park, Chicago, c:1939

Bertha Margaret Snyder was born in Burlington, Iowa. She attended Burlington Junior College, belonged to Alpha Omega, Delta Omicron, Glee Club, Y.W.C.A., Gold Lantern, Vespers Committee, and the Y.W.C.A Circus Committee. Bertha attended Northwestern University from 1928 to 1930 and then intermittently from 1931 to 1936.

Bertha was a student in Loar’s music theory class at Northwestern University. During her time at college, their relationship blossomed and after many years of knowing each other and finally dating, they were married in 1938, a marriage that was to last for 6 years until Lloyd’s death in 1943. As Lloyd pursued his career in musical instrument development, Bertha followed her dream to teach students in 5th and 6th grade.

Through my research, I discovered that Bertha was still alive, but uncovering her whereabouts was another story. Six years after Lloyd’s death, she married Ralph Westerberg who was, like Bertha, a school teacher. With more digging I found that she moved to California, and I then located her address. I wrote to her for a span of six months, but my letters were neither returned nor answered. Bertha had an unlisted phone but with the aid of a local official, I discovered she was again a widow and was able to confirm that she lived at the address I was sending letters to. I was considering a trip to California to meet Bertha personally but her lack of response made me think she would only refuse me at her front door. I didn’t know which way to turn.

Many months after being frustrated by the lack of Bertha’s response, my luthiery assistant, Nancy Hendler, was on her way to Disneyland in Anaheim California, so I made a deal with her that she couldn’t refuse. A few days after Nancy’s departure, I got an excited and bubbly call from her saying: “Guess what?” she screamed, “I met with Bertha. She is very sweet. She didn’t know who you were but she did invite me in for a fruit cup and we spoke for an hour. I told her all about what you were doing but she didn’t know how much she would be able to help you and she recently lost her husband [Ralph]. But, she will see you, here is her phone number.” My heart was pounding. I called Bertha the next day, we talked for half an hour, and I was on a flight bound for California the following morning.

In the years following, Bertha and I became very good friends and my wife and two sons had the chance to visit with her as well. She was quite lonely and lived in a pleasant well-kept house which was adorned with the furniture and possessions from her relationship with both Lloyd and Ralph. The upright piano in her living room was a selection she and Lloyd made, and she played it every day. Nearby was a wooden flat-drawer file cabinet that contained a vast selection of sheet music, including numerous pieces written in hand by Lloyd. These included pieces for duo and trio mandolin ensembles, mandolin and violin pieces, and more. Sitting among these treasures, and hearing her play his music and sing songs they sung together (she loved to sing) was the most mystical, enriching, and exciting experience I have ever had.

Bertha and Lloyd did not have children. She remembered Lloyd as a very sensitive and caring man who enjoyed life, enjoyed a good cigar, and loved music. He would often bring home instruments from Northwestern University and learned to play them over a period of a few months. Then he would bring that instrument back and return with another.

Our relationship grew over the years. Finding in me a kindred soul, we talked almost every day. My administrative assistants and wife understood the need to be supportive to this wonderful woman and often took the role of talking to her at length on the phone when I was either busy or not available.

On my many visits to Bertha’s home, I would bring a mandolin, or play Lloyd’s mandolin, as she would play the piano, and we would sing and share our music, and be warmed by playing together, or she would sing her songs of the past and allow me to venture into her most private place of dreams and memories.

In 1990, while I was on a business trip to Pennsylvania, I called Bertha and got no answer. Occasionally, she would drive to the local market but would return promptly since she had no local family to visit and only had one social friend. I called her back an hour later — no answer. I immediately called a her neighbor who I had come to know over the years. I held on while he ran next door, ran back, and then he reported that the doors were locked and he could see her car in the garage. He was going to get his key (to her house) and investigate further. I held on. Almost fifteen minutes later, he huffed and puffed into the phone that Bertha was inside, she had apparently fallen on her carpet and broken her hip, she couldn’t reach the phone so couldn’t call for help, and she was very dehydrated. He had called 911 from her phone and had to rush back.

I immediately left my Philadelphia meeting and caught a plane for Los Angeles ( had to plead to get them to change my return trip from San Jose to Los Angeles – but the agent finally relented). My son Mark was living in Santa Monica at the time working in the special effects business and he picked me up at the airport and we went to find Bertha at the hospital. She was undergoing hip surgery and we had to wait. During the hours after surgery she was very disoriented. We told her what happened and all she could remember was her difficulty and fear that she couldn’t reach the phone, especially with all her pain.

Her recovery in the hospital was almost two weeks and heightened by the fact they she was so dehydrated at the outset. The hospital staff didn’t feel she could continue without in-home care. I flew home, and drove back two days later to see what I could do to help arrange things. Sadly for Bertha, it was the last time she would see her home, for the medical care that was required necessitated that she be moved to a full care nursing home.

In the many months following, Bertha was saddened by not being in her home and she often spoke about not being able to play her piano. With the hope of putting a smile back on her face, I had her piano moved from her house to the nursing home, but she played it rarely. To keep her from being isolated, I installed a private phone for her so that she and I could be in constant contact, and I visited her more often than I did before. Clearly, this dramatic change in her life was a turning point for her mentally, and I began to notice that she was slowly becoming more distant. I was deeply hurt and saddened to see her there and watch her slip away and feel so helpless in the process.